RPC is Not Dead: Rise, Fall and the Rise of Remote Procedure Calls

Introduction

Remote Procedure Call (RPC) is a design paradigm that allow two entities to communicate over a communication channel in a general request-response mechanism. The definition of RPC has mutated and evolved significantly over the past three decades, and therefore the RPC paradigm is a broad classifying term which refers to all RPC-esque systems that have arisen over the past four decades. The definition of RPC has evolved over the decades. It has moved on from a simple client-server design to a group of inter-connected services. While the initial RPC implementations were designed as tools for outsourcing computation to a server in a distributed system, RPC has evolved over the years to build a language-agnostic ecosystem of applications. The RPC paradigm has been part of the driving force in creating truly revolutionary distributed systems and has given rise to various communication schemes and protocols between diverse systems.

The RPC paradigm has been used to implement our every-day systems. From lower level applications like Network File Systems (Sandberg, Goldberg, Kleiman, Walsh, & Lyon, 1985) and Remote Direct Memory Access (Kalia, Kaminsky, & Andersen, n.d.) to access protocols to developing an ecosystem of microservices, RPC has been used everywhere. RPC has a diversity of applications – SunNFS (Sandberg, Goldberg, Kleiman, Walsh, & Lyon, 1985), Twitter’s Finagle (Eriksen, 2013), Apache Thrift (Prunicki, 2009), Java RMI (Wollrath, Riggs, & Waldo, 1996), SOAP, CORBA (Group, 1991) and Google’s gRPC (Google, n.d.) to name a few.

RPC has evolved over the years. Starting off as a synchronous, insecure, request-response system, RPC has evolved into a secure, asynchronous, resilient paradigm that has influenced protocols and programming designs like HTTP, REST, and just about anything with a request-response system. It has transitioned to an asynchronous, bidirectional, communication mechanism for connecting services and devices across the internet. The initial RPC implementations mainly focused on a local, private network with multiple clients communicating with a server, synchronously waiting for the response from the server. Modern RPC systems have endpoints communicating with each other, asynchronously passing arguments and processing responses, as well as having two-way request-response streams (from client to server, and also from server to client). RPC has influenced various design paradigms and communication protocols.

Remote Procedure Calls

The Remote Procedure Call paradigm can be defined, at a high level, as a set of two communication endpoints connected over a network with one endpoint sending a request and the other endpoint generating a response based on that request. In the simplest terms, it’s a request-response paradigm where the two endpoints/hosts have different address spaces. The endpoint that requests a remote procedure can be referred to as caller and the endpoint that responds to this can be referred to as callee.

The endpoints in the RPC can either be a client and a server, two nodes in a peer-to-peer network, two hosts in a grid computation system, or even two microservices. The RPC communication is not limited to two hosts, rather could have multiple hosts or endpoints involved (Bergstrom & Pandey, 2007).

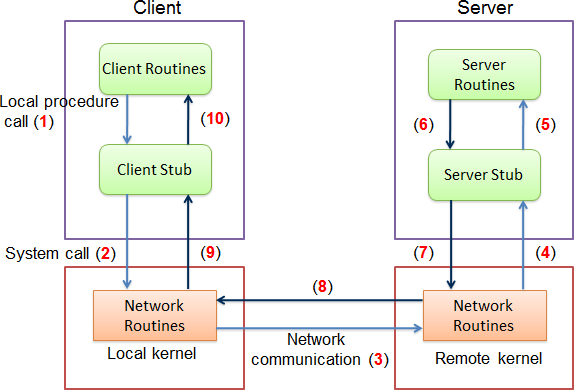

[ Image Source: (Taing, n.d.)]

Figure 1 - Remote Procedure Call.

The simplest RPC implementation looks like Figure 1. In this case, the client (or caller) and the server (or callee) are separated by a physical network. The main components of the system are the client routine/program, the client stub, the server routine/program, the server stub, and the network routines. A stub is a small program that is generally used as a stand-in (or an interface) for a larger program (Rouse, n.d.). A client stub exposes the functionality provided by the server routine to the client routine while the server stub provides a client-like program to the server routine (Taing, n.d.). The client stub takes the input arguments from the client program and returns the result, while the server stub provides input arguments to the server program and gets the results. The client program can only interact with the client stub that provides the interface of the remote server to the client. This stub also serializes input arguments sent to the stub by the client routine. Similarly, the server stub provides a client interface to the server routines as well handling serialization of data sent to the client.

When a client routine performs a remote procedure, it calls the client stub, which serializes the input arguments. This serialized data is sent to the server using OS network routines (TCP/IP) (Taing, n.d.). The data is then deserialized by the server stub and presented to the server routines with the given arguments. The return value from the server routines is serialized again and sent over the network back to the client where it’s deserialized by the client stub and presented to the client routine. This remote procedure is generally hidden from the client routine and it appears as a local procedure to the client. RPC services also require a discovery service/host-resolution mechanism to bootstrap the communication between the client and the server.

One important feature of RPC is different address space (Birrell & Nelson, 1984) for all the endpoints, however, passing the locations to a global storage (Amazon S3, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud Store) is not impossible. In RPC, all the hosts have separate address spaces. They can’t share pointers or references to a memory location in one host. This address space isolation means that all the information is passed in the messages between the host communicating as a value (objects or variables) but not by reference. Since RPC is a remote procedure call, the values sent to the remote host cannot be pointers or references to a local memory. However, passing links to a global shared memory location is not impossible but rather dependent on the type of system (see Applications section for detail).

Originally, RPC was developed as a synchronous request-response mechanism, tied to a specific programming language implementation, with a custom network protocol to outsource computation (Birrell & Nelson, 1984). It had a registry system to register all the servers. One of the earliest RPC-based system (Birrell & Nelson, 1984) was implemented in the Cedar programming language in early 1980’s. The goal of this system was to provide similar programming semantics to local procedure calls. It was developed for a LAN network with an inefficient network protocol and a serialization scheme to transfer information using the said network protocol, this system aimed at executing a procedure (also referred as a method or a function) in a remote address space. The single-threaded synchronous client and the server were accompanied by a registry system used by the servers to bind (or register) their procedures. Clients used this registry system to find a specific server to execute their remote procedures on. This RPC implementation (Birrell & Nelson, 1984) had a very specific use-case. It was built specifically for outsourcing computation between a “Xerox research internetwork”, which was a small, closed, ethernet network with 16-bit addresses (Birrell & Nelson, 1984).

Modern RPC-based systems are language-agnostic, asynchronous, load-balanced systems. Authentication and authorization to these systems have been added as needed along with other security features. Most of these systems have fault-handling built into them as modules and the systems are generally spread all across the internet.

RPC programs operate across a network (or communication channel), therefore they need to handle remote errors and be able to communicate information successfully. Error handling generally varies and is categorized as remote-host or network failure handling. Depending on the type of the system, and the error, the caller (or the callee) returns an error and these errors can be handled accordingly. For asynchronous RPC calls, it’s possible to specify events to ensure progress.

RPC implementations use a serialization (also referred to as marshalling or pickling) scheme on top of an underlying communication protocol (traditionally TCP over IP). These serialization schemes allow both the caller caller and callee to become language agnostic allowing both these systems to be developed in parallel without any language restrictions. Some examples of serialization schemes are JSON, XML, or Protocol Buffers (Google, n.d.).

Modern RPC systems allow different components of a larger system to be developed independently of one another. The language-agnostic nature combined with a decoupling of some parts of the system allows the two components (caller and callee) to scale separately and add new functionalities. This independent scaling of the system might lead to a mesh of interconnected RPC services facilitating one another.

Examples of RPC

RPC has become very predominant in modern systems. Google even performs orders of 10^10 RPC calls per second (Mandel, n.d.). That’s tens of trillions of RPC calls every second. It’s more than the annual GDP of United States (InsideGov, n.d.).

In the simplest RPC systems, a client connects to a server over a network connection and performs a procedure. This procedure could be as simple as return "Hello World" in your favorite programming language. However, the complexity of the of this remote procedure has no upper bound.

An example of a simple RPC server, written in Python 3, is shown below.

from xmlrpc.server import SimpleXMLRPCServer

# a simple RPC function that returns "Hello World!"

def remote_procedure():

return "Hello World!"

server = SimpleXMLRPCServer(("localhost", 8080))

print("RPC Server listening on port 8080...")

server.register_function(remote_procedure, "remote_procedure")

server.serve_forever()

This code for a simple RPC client for the above server, written in Python 3, is as follows.

import xmlrpc.client

with xmlrpc.client.ServerProxy("http://localhost:8080/") as proxy:

print(proxy.remote_procedure())

In the above example, we create a simple function called remote_procedure and bind it to port 8080 on localhost. The RPC client then connects to the server and requests the remote_procedure with no input arguments. The server then responds with the return value returned from executing remote_procedure.

One can even view the three-way handshake as an example of RPC paradigm. The three-way handshake is most commonly used in establishing a TCP connection. Here, a server-side application binds to a port on the server, and adds a hostname resolution entry is added to a DNS server (can be seen as a registry in RPC). Now, when the client has to connect to the server, it requests a DNS server to resolve the hostname to an IP address and the client sends a SYN packet. This SYN packet can be seen as a request to another address space. The server, upon receiving this, returns a SYN-ACK packet. This SYN-ACK packet from the server can be seen as response from the server, as well as a request to establish the connection. The client then responds with an ACK packet.

Evolution of RPC

RPC paradigm was first proposed in 1980’s and still continues as a relevant model of performing distributed computation, which was initially developed for a LAN and now can be implemented on open networks, as web services across the internet. It has had a long and arduous journey to its current state. Here are the three main (overlapping) stages that RPC went through.

The Rise: All Hail RPC (Early 1970’s - Mid 1980’s)

RPC started off strong. With RFC 674 (Postel & White, 1974) and RFC 707 (Postel & White, 1974; White, 1975) coming out and specifying the design of Remote Procedure Calls, followed by Nelson et. al (Birrell & Nelson, 1984) coming up with a first RPC implementation for the Cedar programming language, RPC revolutionized systems in general and gave rise to one of the earliest distributed systems.

With these early achievements, people started using RPC as the defacto design choice. It became a Holy Grail in the systems community for a few years after the first implementation.

The Fall: RPC is Dead (Late 1970’s - Late 1990’s)

RPC, despite being an initial success, wasn’t without flaws. Within a year of its inception, the limitations of RPC started to catch up to it. RFC 684 criticized RPC for latency, failures, and overhead cost. It also focussed on message-passing systems as an alternative to RPC design. In 1988, Tenenbaum et. al presented similar concerns with RPC (Tanenbaum & van Renesse, 1987). This talked about problems with heterogeneous devices, message passing as an alternative, packet loss, network failure, RPC’s synchronous nature, and highlighted that RPC is not a one-size-fits-all model.

In 1994, A Note on Distributed Computing was published. This paper claimed RPC to be “fundamentally flawed” (Waldo, Wyant, Wollrath, & Kendall, 1997). It talked about a unified object view and cited four main problems with dividing these objects for distributed computing in RPC: communication latency, address space separation, partial failures and concurrency issues (resulting from accessing same remote object by two concurrent client requests). Most of these problems (except partial failures) were inherently associated with distributed computing itself, but partial failures for RPC systems meant that progress might not always be possible in an RPC system.

This era wasn’t a dead end for RPC, though. Some of the preliminary designs for modern RPC systems were introduced in this era. Perhaps, the earliest system in this era was SunRPC (Sandberg, Goldberg, Kleiman, Walsh, & Lyon, 1985) used for the Sun Network File System (NFS). Soon to follow SunRPC was CORBA (Group, 1991) which was followed by Java RMI (Wollrath, Riggs, & Waldo, 1996).

However, the initial implementations of these systems were riddled with various issues and design flaws. For instance, Java RMI didn’t handle network failures and assumed a reliable network with zero-latency (Wollrath, Riggs, & Waldo, 1996).

The Rise, Again: Long Live RPC (Late 1990’s - Today)

Despite facing problems in its early days, RPC withstood the test of time. Researchers realized the limitations of RPC and focussed on rectifying and instead of enforcing RPC, they started to use RPC in applications where it was needed. Implementers of RPC systems started adding exception-handling, asyncronous processing, network failure handling, and support for heterogeneity between different languages/devices to RPC.

In this era, SunRPC went through various additions and became came to be known as Open Network Computing RPC (ONC RPC). CORBA and RMI have also undergone various modifications as internet standards were set.

A new breed of RPC also started in this era, Async (asynchronous) RPC, giving rise to systems that use futures and promises, like Finagle (Eriksen, 2013) and Cap’n Proto (post-2010).

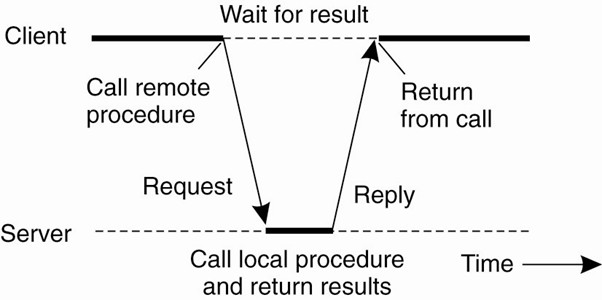

[ Image Source: (Norman, 2015)]

Figure 2 - Synchronous RPC.

[ Image Source: (Norman, 2015)]

Figure 3 - Asynchronous RPC.

A traditional, synchronous RPC is a blocking operation while an asynchronous RPC is a non-blocking operation (Dewan, 2006). Figure 2 shows a synchronous RPC call while Figure 3 shows an asynchronous RPC call. In synchronous RPC, the client sends a request to the server and then blocks waiting for the server to perform its computation and return the result. The client is only able to proceed after getting the result from the server. In an asynchronous RPC, the client performs a request to the server and waits only for the acknowledgment of the delivery of input parameters/arguments. After this, the client proceeds onwards and when the server is finished processing, it sends an interrupt to the client. The client receives this message from the server, receives the results, and continues.

Asynchronous RPC makes it possible to separate the remote call from the return value, making it possible to write a single-threaded client to handle multiple RPC calls at the specific intervals it needs to process (“Asynchronous RPC,” 2006). It also allows for easier handling of slow clients/servers as well as transferring large data easily (due to their incremental nature) (“Asynchronous RPC,” 2006).

In the post-2000 era, MAUI (Cuervo et al., 2010), Cap’n Proto (Kenton, n.d.), gRPC (Google, n.d.), Thrift (Prunicki, 2009) and Finagle (Eriksen, 2013) have been released, which have significantly boosted the widespread use of RPC.

Most of these newer systems include Interface Description Languages (IDLs). These IDLs specify the common protocols and interfacing languages that can be used to transfer information between clients and servers written in different programming languages, making these RPC implementations language-agnostic. Some of the most common IDLs are JSON, XML, and ProtoBufs.

A high-level overview of some of the most important RPC implementation is as follows.

Java Remote Method Invocation

Java RMI (Java Remote Method Invocation) (Pitt & McNiff, 2001) is a Java implementation for performing RPC (Remote Procedure Calls) between a client and a server. The client using a stub passes via a socket connection the information over the network to the server that contains remote objects. The Remote Object Registry (ROR) (Wollrath, Riggs, & Waldo, 1996) on the server contains the references to objects that can be accessed remotely and through which the client will connect to. The client can then request the invocation of methods on the server which responds with an answer.

RMI provides some security by being encoded but not encrypted, though that can be augmented by tunneling over a secure connection or other methods. Moreover, RMI is very specific to Java. It cannot be used to take advantage of the language-independence feature that is inherent to most RPC implementations. Perhaps the main problem with RMI is that it doesn’t provide access transparency. This means that a programmer (not the client program) cannot distinguish between the local objects or the remote objects making it relatively difficult handle partial failures in the network (Setia, n.d.).

CORBA

CORBA (Common Object Request Broker Architecture) (Group, 1991) was created by the Object Management Group (CORBA, n.d.) to allow for language-agnostic communication among multiple computers. It is an object-oriented model defined via an Interface Definition Language (IDL) and the communication is managed through an Object Request Broker (ORB). This ORB acts as a broker for objects. CORBA can be viewed as a language-independent RMI system where each client and server have an ORB by which they communicate. The benefits of CORBA is that it allows for multi-language implementations that can communicate with each other, but much of the criticism around CORBA relates to poor consistency among implementations and it’s relatively outdated by now. Moreover, CORBA suffers from same access transparency issues as Java RMI.

XML-RPC and SOAP

The XML-RPC specifications (Weiner, 1999) performs an HTTP Post request to a server formatted as XML composed of a header and payload that calls only one method. It was originally released in the late 1990’s and unlike RMI, it provides transparency by using HTTP as a transparent mechanism.

The header has to provide the basic information, like user agent and the size of the payload. The payload has to initiate a methodCall structure by specifying the name via methodName and associated parameter values. Parameters for the method can be scalar, structures or (recursive) arrays. The types of scalar can be one of i4, int, boolean, string, double, dateTime.iso8601 or base64. The scalars are used to create more complex structures and arrays.

Below is an example as provided by the XML-RPC documentation (Weiner, 1999):

POST /RPC2 HTTP/1.0

User-Agent: Frontier/5.1.2 (WinNT)

Host: betty.userland.com

Content-Type: text/xml

Content-length: 181

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<methodCall>

<methodName>examples.getStateName</methodName>

<params>

<param>

<value><i4>41</i4></value>

</param>

</params>

</methodCall>

The response to a request will have the methodResponse with params and values, or a fault with the associated faultCode in the case of an error (Weiner, 1999):

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Connection: close

Content-Length: 158

Content-Type: text/xml

Date: Fri, 17 Jul 1998 19:55:08 GMT

Server: UserLand Frontier/5.1.2-WinNT

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<methodResponse>

<params>

<param>

<value><string>South Dakota</string></value>

</param>

</params>

</methodResponse>

SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol) is a successor of XML-RPC as a web-services protocol for communicating between a client and server. It was initially designed by a group at Microsoft (Ferguson, n.d.). The SOAP message is an XML-formatted message composed of an envelope inside which a header and a payload are provided(just like XML-RPC). The payload of the message contains the request and response of the message, which is transmitted over HTTP or SMTP (unlike XML-RPC).

SOAP can be viewed as the superset of XML-RPC that provides support for more complex authentication schemes (Jones, 2014) as well as its support for WSDL (Web Services Description Language), allowing easier discovery and integration with remote web services (Jones, 2014).

The benefit of SOAP is that it provides the flexibility for transmission over multiple transport protocols. The XML-based messages allow SOAP to become language agnostic, though parsing such messages could become a bottleneck.

Thrift

Thrift is an asynchronous RPC system created by Facebook which is now part of the Apache Foundation (Prunicki, 2009). It is a language-agnostic Interface Description Language (IDL) by which one generates the code for the client and server. It provides the opportunity for compressed serialization by customizing the protocol and the transport after the description file has been processed.

Perhaps, the biggest advantage of Thrift is that its binary data format has a very low overhead. It has a relatively lower transmission cost (compared to other alternatives like SOAP) (Maheshwar, 2013) making it very efficient for large amounts of data transfer.

Finagle

Finagle is a fault-tolerant, protocol-agnostic runtime for doing RPC and high-level API calls for composing futures (see Async RPC section), with RPC calls generated under the hood. It was created by Twitter and is written in Scala to run on the JVM. It is based on three object types: Service objects, Filter objects, and Future objects (Eriksen, 2013).

Future objects act by asynchronously requesting computation that would return a response at some time in the future. These Future objects are the main communication mechanism in Finagle. All the inputs and the output are represented as Future objects.

Service objects endpoints that return a Future upon processing a request. These Service objects can be viewed as the interfaces used to implement a client or a server.

A sample Finagle server that reads a request and returns the version of the request is shown below. This example is taken from the Finagle documentation (Twitter, 2016)

import com.twitter.finagle.{Http, Service}

import com.twitter.finagle.http

import com.twitter.util.{Await, Future}

object Server extends App {

val service = new Service[http.Request, http.Response] {

def apply(req: http.Request): Future[http.Response] =

Future.value(

http.Response(req.version, http.Status.Ok)

)

}

val server = Http.serve(":8080", service)

Await.ready(server)

}

A Filter object transforms requests for further processing in case additional customization is required from a request. These provide program-independent operations like, timeouts, etc. They take in a Service and provide a new Service object with the applied Filter. Aggregating multiple Filters is also possible in Finagle.

A sample timeout Filter that takes in a service and creates a new service with timeouts is shown below. This example is taken from the Finagle documentation (Twitter, 2016)

import com.twitter.finagle.{Service, SimpleFilter}

import com.twitter.util.{Duration, Future, Timer}

class TimeoutFilter[Req, Rep](timeout: Duration, timer: Timer)

extends SimpleFilter[Req, Rep] {

def apply(request: Req, service: Service[Req, Rep]): Future[Rep] = {

val res = service(request)

res.within(timer, timeout)

}

}

Open Network Computing RPC (ONC RPC)

ONC was originally introduced as SunRPC (Sandberg, Goldberg, Kleiman, Walsh, & Lyon, 1985) for the Sun NFS. The Sun NFS system had a stateless server, with client-side caching, unique file handlers, and supported NFS read, write, truncate, unlink, etc operations. However, SunRPC was later revised as ONC in 1995 (Srinivasan, 1995) and then in 2009 (Thurlow, 2009). The IDL used in ONC (and SunRPC) is External Data Representation (XDR), a serialization mechanism specific to networks communication and therefore, ONC is limited to applications like Network File Systems.

Mobile Assistance Using Infrastructure (MAUI)

The MAUI project (Cuervo et al., 2010), developed by Microsoft is a computation offloading system for mobile systems. It’s an automated system that offloads a mobile code to a dedicated infrastructure in order to increase the battery life of the mobile device, minimize the load on the programmer, and perform any complex computations offsite. MAUI uses RPC as the communication protocol between the mobile and the infrastructure.

gRPC

gRPC is a multiplexed, bi-directional streaming RPC protocol developed Google and Square. The IDL for gRPC is Protocol Buffers (also referred as ProtoBuf) and is meant as a public replacement fro Stubby, ARCWire, and Sake (Surtani & Ho, n.d.). More details on Protocol Buffers, Stubby, ARCWire, and Sake are available in our gRPC chapter (Grosu, Abdul Rehman, Anderson, Pai, & Miller, n.d.).

gRPC provides a platform for scalable, bi-directional streaming using both synchronized and asynchronous communication.

In a general RPC mechanism, the client initiates a connection to the server and only the client can request while the server can only respond to the incoming requests. However, in bi-directional gRPC streams, although the initial connection is initiated by the client (call it endpoint 1), once the connection is established, both the server (call it endpoint 2) and the endpoint 1 can send requests and receive responses. This significantly eases the development where both endpoints are communicating with each other (like, grid computing). It also saves the hassle of creating two separate connections between the endpoints (one from endpoint 1 to endpoint 2 and another from endpoint 2 to endpoint 1) since both streams are independent.

gRPC multiplexes the requests over a single connection using header compression. This makes it possible for gRPC to be used for mobile clients where battery life and data usage are important. The core library is in C – except for Java and Go – and surface APIs are implemented for all the other languages connecting through it (Google, n.d.).

Since Protocol Buffers have been utilized by many individuals and companies, gRPC makes it natural to extend their RPC ecosystems via gRPC. Companies like Cisco, Juniper, and Netflix (Google, n.d.) have found it practical to adopt it. A majority of the Google Public APIs, like their places and maps APIs, have been ported to gRPC ProtoBuf (Google, n.d.) as well.

More details about gRPC and bi-directional streaming can be found in our gRPC chapter (Grosu, Abdul Rehman, Anderson, Pai, & Miller, n.d.)

Cap’n Proto

CapnProto (Kenton, n.d.) is a data interchange RPC system that bypasses the data-encoding step to significantly improve the performance of calls. It is developed by the original author of gRPC’s ProtoBuf, but since it uses bytes (binary data) for encoding/decoding, it outperforms gRPC’s ProtoBuf. It uses futures and promises to combine various remote operations into a single operation to save on transportation round-trips. This means if an client calls a function foo and then calls another function bar on the output of foo, Cap’n Proto will aggregate these two operations into a single bar(foo(x)) where x is the input to the function foo (Kenton, n.d.). This saves multiple roundtrips, especially in object-oriented programs.

The Heir to the Throne: gRPC or Thrift

Although there are many candidates to be considered as top contenders for RPC throne, most of these are targeted for a specific type of application. ONC is generally specific to the Network File System (though it’s being pushed as a standard), Cap’n Proto is relatively new and untested, MAUI is specific to mobile systems, the open-source Finagle is primarily being used at Twitter (not widespread), and the Java RMI simply doesn’t even come close due to its transparency issues.

Probably, the most powerful, and practical systems out there are Apache Thrift and Google’s gRPC, primarily because these two systems cater to a large number of programming languages, have a significant performance benefit over other techniques, and are being actively developed.

Thrift was actually released a few years ago, while the first stable release for gRPC came out in August 2016. However, despite being released for some time, Thrift is currently less popular than gRPC (Trends, n.d.).

gRPC (Google, n.d.) and Thrift, both, support most of the popular languages, including Java, C/C++, and Python. Thrift supports other languages, like Ruby, Erlang, Perl, Javascript, Node.js and OCaml while gRPC currently supports Node.js and Go.

The gRPC core is written in C (with the exception of Java and Go) and wrappers are written in other languages to communicate with the core, while the Thrift core is written in C++.

gRPC also provides easier bidrectional streaming communication between the caller and callee. The client generally initiates the communication (Google, n.d.) and once the connection is established the client and the server can perform reads and writes independently of each other. However, bi-directional streaming in Thrift might be a little difficult to handle, since it focuses explicitly on a client-server model. To enable bidirectional, async streaming, one may have to run two separate systems (Google, n.d.).

Thrift provides exception-handling as a message while the programmer has to handle exceptions in gRPC. In Thrift, exceptions can be returned built into the message, while in gRPC, the programmer explicitly defines this behavior. This Thrift exception-handling makes it easier to write client-side applications.

Although custom authentication mechanisms can be implemented in both these system, gRPC comes with Google-backed authentication using SSL/TLS and Google Tokens (Google, n.d.).

Moreover, gRPC-based network communication is done using HTTP/2. HTTP/2 makes it feasible for communicating parties to multiplex network connections using the same port. This is more efficient (in terms of memory usage) as compared to HTTP/1.1. Since gRPC communication is done HTTP/2, it means that gRPC can easily multiplex different services. As for Thrift, multiplexing services is possible, however, due to lack of support from underlying transport protocol, it is performed using a TMultiplexingProcessor class (in code) (Yu, n.d.).

However, both gRPC and Thrift allow async RPC calls. This means that a client can send a request to the server and continue with its execution and the response from the server is processed it arrives.

The major comparison between gRPC and Thrift can be summed in this table.

| Comparison | Thrift | gRPC |

|---|---|---|

| License | Apache2 | BSD |

| Sync/Async RPC | Both | Both |

| Supported Languages | C++, Java, Python, PHP, Ruby, Erlang, Perl, Haskell, C#, Cocoa, JavaScript, Node.js, Smalltalk, and OCaml | C/C++, Python, Go, Java, Ruby, PHP, C#, Node.js, Objective-C |

| Core Language | C++ | C |

| Exceptions | Allows being built in the message | Implemented by the programmer |

| Authentication | Custom | Custom + Google Tokens |

| Bi-Directionality | Not straightforward | Straightforward |

| Multiplexing | Possible via TMultiplexingProcessor class |

Possible via HTTP/2 |

Although, it’s difficult to specifically choose one over the other, with the increasing popularity of gRPC, and the fact that it’s still in early stages of development, the general trend (Trends, n.d.) over the past year has started to shift in favor of gRPC and it’s giving Thrift a run for its money. It may not be a useful metric, but on average gRPC was searched for three times more frequently than Thrift (Trends, n.d.).

Note: This comparison was performed in December 2016 so the results are expected to change over time.

Applications

Since its inception, various papers have been published on applying the RPC paradigm to different domains, as well as using RPC implementations to create new systems. Here are some of applications and systems that incorporate RPC.

Shared State and Persistence Layer

One major limitation (and advantage) of RPC is considered the separate address space of all the machines in the network. This means that pointers or references to a data object cannot be passed between the caller and the callee. Therefore, Interweave (Chen, Dwarkadas, Parthasarathy, Pinheiro, & Scott, 2000; Tang, Chen, Dwarkadas, & Scott, 2004; Chen, Tang, Chen, Dwarkadas, & Scott, 2002) is a middleware system that allows scalable sharing of arbitrary datatypes and language-independent processes running on heterogeneous hardware. Interweave is specifically designed and is compatible with RPC-based systems and allows easier access to the shared resources between different applications using memory blocks and locks.

Although research has been done in order to ensure a global shared state for an RPC-based system, these systems tend to take away the sense of independence and modularity between the caller and the callee by using a shared storage instead of a separate address space.

GridRPC

Grid computing is one of the most widely used applications of the RPC paradigm. At a high level, it can be seen as a mesh (or a network) of computers connected with each other to form a grid such that each system can leverage resources from any other system in the network.

In the GridRPC paradigm, each computer in the network can act as the caller or the callee depending on the amount of resources required (Caniou et al., 2008). It’s also possible for the same computer to act as the caller as well as the callee for different computations.

Some of the most popular implementations that allow one to have GridRPC-compliant middleware are GridSolve (YarKhan, Dongarra, & Seymour, 2007; Hardt, Seymour, Dongarra, Zapf, & Ruitter, 2012) and Ninf-G (Tanaka, Nakada, Sekiguchi, Suzumura, & Matsuoka, 2003). Ninf is relatively older than GridSolve and was first published in the late 1990’s. It’s a simple RPC layer that also provides authentication and secure communication between the two parties. GridSolve, on the other hand, is relatively complex and provides a middleware for the communications using a client-agent-server model.

Mobile Systems and Computation Offloading

Mobile systems have become very powerful these days. With multi-core processors and gigabytes of RAM, they can undertake relatively complex computations without a hassle. Due to this advancement, they consume a larger amount of energy and hence, their batteries, despite becoming larger, drain quickly with usage. Moreover, mobile data (network bandwidth) is still limited and expensive. Due to these requirements, it’s better to offload mobile computations from mobile systems when possible. RPC plays an important role in the communication for this computation offloading. Some of these services use Grid RPC technologies to offload this computation. Whereas, other technologies use an RMI (Remote Method Invocation) system for this.

The Ibis Project (Ibis, n.d.) builds an RMI (similar to JavaRMI) and GMI (Group Method Invocation) model to facilitate outsourcing computation. Cuckoo (Zhou, Zhang, Ye, & Du, 2016) uses this Ibis communication middleware to offload computation from applications (built using Cuckoo) running on Android smartphones to remote Cuckoo servers.

The Microsoft’s MAUI Project (Cuervo et al., 2010) uses RPC communication and allows partitioning of .NET applications and “fine-grained code offload to maximize energy savings with minimal burden on the programmer”. MAUI decides the methods to offload to the external MAUI server at runtime.

Async RPC, Futures and Promises

Remote Procedure Calls can be asynchronous. Not only that but these async RPCs play in integral role in the futures and promises. Futures and promises are programming constructs that where a future is seen as variable/data/return type/error while a promise is seen as a future that doesn’t have a value, yet. We follow Finagle’s (Eriksen, 2013) definition of futures and promises, where the promise of a future (an empty future) is considered as a request while the async fulfillment of this promise by a future is seen as the response. This construct is primarily used for asynchronous programming.

Perhaps the most renowned systems using this type of RPC model are Twitter’s Finagle (Eriksen, 2013) and Cap’n Proto (Kenton, n.d.).

RPC in Microservices Ecosystem

RPC implementations have moved from a one-server model to multiple servers and on to dynamically-created, load-balanced microservices. RPC started as separate implementations of REST, Streaming RPC, MAUI, gRPC, Cap’n Proto, and has now made it possible for integration of all these implementations as a single abstraction as a user endpoint. The endpoints are the building blocks of microservices. A microservice is usually service with a very simple, well-defined purpose, written in almost any language that interacts with other microservices to give the feel of one large monolithic service. These microservices are language-agnostic. One microservice for airline tickets written in C/C++, might be communicating with a number of other microservices for individual airlines written in different languages (Python, C++, Java, Node.js) using a language-agnostic, asynchronous, RPC framework like gRPC (Google, n.d.) or Thrift (Prunicki, 2009).

The use of RPC has allowed us to create new microservices on-the-fly. The microservices can not only created and bootstrapped at runtime but also have inherent features like load-balancing and failure-recovery. This bootstrapping might occur on the same machine, adding to a Docker container (Merkel, 2014), or across a network (using any combination of DNS, NATs or other mechanisms).

RPC can be defined as the “glue” that holds all the microservices together (Mueller, 2015). This means that RPC is one of the primary communication mechanism between different microservices running on different systems. A microservice requests another microservice to perform an operation/query. The other microservice, upon receiving such request, performs an operation and returns a response. This operation could vary from a simple computation to invoking another microservice creating a series of RPC events to creating new microservices on the fly to dynamically load balance the microservices system. These microservices are language-agnostic. One microservice could be written in C/C++, another one could be in different languages (Python, C++, Java, Node.js) and they all might be communicating with each other using a language-agnostic, asynchronous, performant RPC framework like gRPC (Google, n.d.) or Thrift (Prunicki, 2009).

An example of a microservices ecosystem that uses futures/promises is Finagle (Eriksen, 2013) at Twitter.

Security in RPC

The initial RPC implementation (Birrell & Nelson, 1984) was developed for an isolated LAN network and didn’t focus much on security. There’re various attack surfaces in that model, from the malicious registry to a malicious server, to a client targeting for Denial-of-Service to Man-in-the-Middle attack between client and server.

As time progressed and internet evolved, new standards came along, and RPC implementations became much more secure. Security, in RPC, is generally added as a module or a package. These modules have libraries for authentication and authorization of the communication services (caller and callee). These modules are not always bug-free and it’s possible to gain unauthorized access to the system. Efforts are being made to rectify these situations by the security in general, using code inspection and bug bounty programs to catch these bugs beforehand. However, with time new bugs arise and this cycle continues. It’s a vicious cycle between attackers and security experts, both of whom tries to outdo their opponent.

For example, the Oracle Network File System uses Secure RPC (Oracle, n.d.) to perform authentication in the NFS. This Secure RPC uses a Diffie-Hellman authentication mechanism with DES encryption to allow only authorized users to access the NFS. Similarly, Cap’n Proto (Kenton, n.d.) claims that it is resilient to memory leaks, segfaults, and malicious inputs and can be used between mutually untrusting parties. However, in Cap’n Proto “the RPC layer is not robust against resource exhaustion attacks, possibly allowing denials of service”, nor has it undergone any formal verification (Kenton, n.d.).

Although, it’s possible to come up with a Threat Model that would make an RPC implementation insecure to use, one has to understand that using any distributed system increases the attack surface anyways and claiming one paradigm to be more secure than another would be a biased statement, since paradigms are generally an idea and it depends on different system designers to use these paradigms to build their systems and take care of features specific to real systems, like security and load-balancing. There’s always a possibility of rerouting a request to a malicious server (if the registry gets hacked), or there’s no trust between the caller and callee. However, we maintain that RPC paradigm is not secure or insecure (for that matter), and that the most secure systems are the ones that are in an isolated environment, disconnected from the public internet with a self-destruct mechanism (Sarma, Weis, & Engels, 2002) in place, in an impenetrable bunker, and guarded by the Knights Templar (they don’t exist! Well, maybe Fort Meade comes close).

Discussion

The RPC paradigm shines the most in request-response mechanisms. Futures and Promises also appear to a new breed of RPC. This leads one to question, as to whether every request-response system is a modified implementation to of the RPC paradigm, or does it actually bring anything new to the table? These modern communication protocols, like HTTP and REST, might just be a different flavor of RPC. In HTTP, a client requests a web page (or some other content), the server then responds with the required content. The dynamics of this communication might be slightly different from your traditional RPC, however, an HTTP Stateless server adheres to most of the concepts behind the RPC paradigm. Similarly, consider sending a request to your favorite Google API. Say, you want to translate your latitude/longitude to an address using their Reverse Geocoding API, or maybe want to find out a good restaurant in your vicinity using their Places API, you’ll send a request to their server to perform a procedure that would take a few input arguments, like the coordinates, and return the result. Even though these APIs follow a RESTful design, it appears to be an extension to the RPC paradigm.

The RPC paradigm has evolved over time. It has evolved to the extent that, currently, it’s become very difficult differentiate RPC from non-RPC. With each passing year, the restrictions and limitations of RPC evolve. Current RPC implementations even have the support for the server to request information from the client to respond to these requests and vice versa (bidirectionality). This bidirectional nature of RPCs have transitioned RPC from simple client-server model to a set of endpoints communicating with each other.

For the past four decades, researchers and industry leaders have tried to come up with their definition of RPC. The proponents of RPC paradigm view every request-response communication as an implementation the RPC paradigm while those against RPC try to explicitly enumerate the limitations of RPC. These limitations, however, seem to slowly vanish as new RPC models are introduced with time. RPC supporters consider it as the Holy Grail of distributed systems. They view it as the foundation of modern distributed communication. From Apache Thrift and ONC to HTTP and REST, they advocate it all as RPC while REST developers have strong opinions against RPC.

Moreover, with modern global storage mechanisms, the need for RPC systems to have a separate address space seems to be slowly dissolving and disappearing into thin air. So, the question remains what is RPC and what is not RPC? This is an open-ended question. There is no unanimous agreement about what RPC should look like, except that it has communication between two endpoints. What we think of RPC is:

In the world of distributed systems, where every individual component of a system, be it a hard disk, a multi-core processor, or a microservice, is an extension of the RPC, it’s difficult to come with a concrete definition of the RPC paradigm. Therefore, anything loosely associated with a request-response mechanism can be considered as RPC.

**RPC is not dead, long live RPC!**

References

- Sandberg, R., Goldberg, D., Kleiman, S., Walsh, D., & Lyon, B. (1985). Design and implementation of the Sun network filesystem. In Proceedings of the Summer USENIX conference (pp. 119–130).

- Kalia, A., Kaminsky, M., & Andersen, D. G. FaSST: Fast, Scalable and Simple Distributed Transactions with Two-Sided (RDMA) Datagram RPCs. In 12th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 16) (pp. 185–201). USENIX Association.

- Eriksen, M. (2013). Your server as a function. In Proceedings of the Seventh Workshop on Programming Languages and Operating Systems (p. 5). ACM.

- Prunicki, A. (2009). Apache Thrift.

- Wollrath, A., Riggs, R., & Waldo, J. (1996). A Distributed Object Model for the Java\^ T\^ M System.

- Group, O. M. (1991). The Common Object Request Broker: Architecture and Specification. OMG Document Number 91.12.1.

- Google. gRPC. Retrieved from http://www.grpc.io/

- Bergstrom, E., & Pandey, R. (2007). Anycast-RPC for Wireless Sensor Networks. In 2007 IEEE International Conference on Mobile Adhoc and Sensor Systems (pp. 1–8). IEEE.

- Taing, N. Remote Procedure Call (RPC). Retrieved from http://lycog.com/distributed-systems/remote-procedure-call/

- Rouse, M. stub. WhatIs. Retrieved from http://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/stub

- Birrell, A. D., & Nelson, B. J. (1984). Implementing remote procedure calls. ACM Transactions on Computer Systems (TOCS), 2(1), 39–59.

- Mandel, M. Scalable Realtime Microservices with Kubernetes and gRPC. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xb8u2s7cxzg&t=486s

- InsideGov. 2016 United States Budget Estimate. InsideGov. Retrieved from http://federal-budget.insidegov.com/l/119/2016-Estimate

- Postel, J., & White, J. E. (1974). RFC 674: Procedure call documents: Version 2.

- White, J. E. (1975). RFC 707: A high-level framework for network-based resource sharing. December.

- Tanenbaum, A. S., & van Renesse, R. (1987). A critique of the remote procedure call paradigm.

- Waldo, J., Wyant, G., Wollrath, A., & Kendall, S. (1997). A note on distributed computing. In Mobile Object Systems Towards the Programmable Internet (pp. 49–64). Springer.

- Norman, S. (2015). Communication Fundamentals. SlideShare. Retrieved from http://slideplayer.com/slide/8555756/

- Dewan, P. (2006). Synchronous vs Asynchronous. UNC. Retrieved from http://www.cs.unc.edu/ dewan/242/s07/notes/ipc/node9.html

- Asynchronous RPC. (2006). Microsoft. Retrieved from https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/windows/desktop/aa373550(v=vs.85).aspx

- Cuervo, E., Balasubramanian, A., Cho, D.-ki, Wolman, A., Saroiu, S., Chandra, R., & Bahl, P. (2010). MAUI: making smartphones last longer with code offload. In Proceedings of the 8th international conference on Mobile systems, applications, and services (pp. 49–62). ACM.

- Kenton. Is Cap’n Proto Secure? Retrieved from https://capnproto.org/faq.html#is-capn-proto-secure

- Pitt, E., & McNiff, K. (2001). Java. rmi: The Remote Method Invocation Guide. Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.

- Setia, S. Remote Object Invocation. QMU. Retrieved from https://cs.gmu.edu/ setia/cs707/slides/rmi-imp.pdf

- CORBA. CORBA-OMG. Retrieved from http://www.corba.org/

- Weiner, D. (1999). XML-RPC. QMU. Retrieved from http://xmlrpc.scripting.com/spec.html

- Ferguson, D. Exclusive .NET Developer’s Journal "Indigo" Interview with Microsoft’s Don Box. Retrieved from http://dotnet.sys-con.com/node/45908

- Jones, M. (2014). XML-RPC. Quora. Retrieved from https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-difference-between-xml-rpc-and-soap

- Maheshwar, C. (2013). Apache THRIFT: A Much Needed Tutorial. Digital Madness. Retrieved from http://digital-madness.in/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/BSD_08_2013.8-18.pdf

- Twitter. (2016). Finagle-Quickstart. Twitter. Retrieved from https://twitter.github.io/finagle/guide/Quickstart.html

- Srinivasan, R. (1995). RFC 1831: RPC: Remote Procedure Call Protocol Specification Version 2.

- Thurlow, R. (2009). RFC 5531: RPC: Remote Procedure Call Protocol Specification Version 2.

- Surtani, M., & Ho, A. gRPC: The Story of Microservices at Square. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-2sWDr3Z0Wo

- Grosu, P., Abdul Rehman, M., Anderson, E., Pai, V., & Miller, H. gRPC. Programming Models for Distributed Computation. Github. Retrieved from http://dist-prog-book.com/chapter/1/gRPC.html

- Google. gRPC core APIs. Retrieved from https://github.com/grpc/grpc/tree/master/src/core

- Google. About gRPC. Retrieved from http://www.grpc.io/about/

- Google. Google APIs. Retrieved from https://github.com/googleapis/googleapis/

- Trends, G. Remote Procedure Call (RPC). Retrieved from https://www.google.com/trends/explore?cat=31&date=today%2012-m&q=apache%20thrift,grpc&hl=en-US

- Google. gRPC Documentation. Retrieved from http://www.grpc.io/docs/

- Google. GRPC Authentication. Quora. Retrieved from https://www.quora.com/Is-GRPC-better-than-Thrift

- Google. GRPC Authentication. Retrieved from http://www.grpc.io/docs/guides/auth.html

- Yu, L. Added service multiplexing support. Github. Retrieved from https://github.com/eleme/thriftpy/pull/88/commits/0877531f9246ca993c1d9af5d29cd009ee6ec7d4

- Chen, D. Q., Dwarkadas, S., Parthasarathy, S., Pinheiro, E., & Scott, M. L. (2000). Interweave: A middleware system for distributed shared state. In International Workshop on Languages, Compilers, and Run-Time Systems for Scalable Computers (pp. 207–220). Springer.

- Tang, C., Chen, D. Q., Dwarkadas, S., & Scott, M. L. (2004). Integrating remote invocation and distributed shared state. In Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium, 2004. Proceedings. 18th International (p. 30). IEEE.

- Chen, D. Q., Tang, C., Chen, X., Dwarkadas, S., & Scott, M. L. (2002). Multi-level shared state for distributed systems. In Parallel Processing, 2002. Proceedings. International Conference on (pp. 131–140). IEEE.

- Caniou, Y., Caron, E., Desprez, F., Nakada, H., Tanaka, Y., & Seymour, K. (2008). High performance GridRPC middleware. Recent Developments in Grid Technology and Applications, Nova Science Publishers, 141–181.

- YarKhan, A., Dongarra, J., & Seymour, K. (2007). Gridsolve: The evolution of a network enabled solver. In Grid-Based Problem Solving Environments (pp. 215–224). Springer.

- Hardt, M., Seymour, K., Dongarra, J., Zapf, M., & Ruitter, N. V. (2012). Interactive Grid-access using Gridsolve and giggle. Computing and Informatics, 27(2), 233–248.

- Tanaka, Y., Nakada, H., Sekiguchi, S., Suzumura, T., & Matsuoka, S. (2003). Ninf-G: A reference implementation of RPC-based programming middleware for Grid computing. Journal of Grid Computing, 1(1), 41–51.

- Ibis. Ibis Communication middleware. Retrieved from https://www.cs.vu.nl/ibis/rmi.html

- Zhou, Z., Zhang, H., Ye, L., & Du, X. (2016). Cuckoo: flexible compute-intensive task offloading in mobile cloud computing. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing.

- Merkel, D. (2014). Docker: lightweight linux containers for consistent development and deployment. Linux Journal, 2014(239), 2.

- Mueller, J. (2015). Delving Into the Microservices Architecture. Retrieved from http://blog.smartbear.com/microservices/delving-into-the-microservices-architecture/

- Oracle. Overview of Secure RPC. Retrieved from https://docs.oracle.com/cd/E23823_01/html/816-4557/auth-2.html

- Sarma, S. E., Weis, S. A., & Engels, D. W. (2002). RFID systems and security and privacy implications. In International Workshop on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems (pp. 454–469). Springer.