Distributed Programming Languages

Problems of Distributed Programming

There are problems that exist in distributed system environments that do not exist in single-machine environments. Partial failure, concurrency, and latency are three problems that make distributed computing fundamentally different from local computing. In order to understand the design decisions behind programming languages and systems for distributed computing, it is necessary to discuss these three problems that make distributed computing unique. In this section, we present an overview of these three problems and their impact on distributed programming models.

Partial Failure

In the case of a crash on a local environment, either the machine has failed (total failure), or the source of the crash can be learned from a central resource manager such as the operating system. (Waldo, Wyant, Wollrath, & Kendall, 1997) If an application consists of multiple communicating processes partial failure is possible, however because the cause of the partial failure can be determined, this kind of partial failure can be repaired given the operating system’s knowledge. For example, a process can be restored based on a checkpoint, another process in the application can query the operating system about the failed process’ state, etc.

Because failure in a distributed setting involves another player, the network, it is impossible in most cases to determine the cause of failure. In a distributed environment, there is no (reliable) central manager that can report on the state of all components. Further, due to the inherent concurrency in a distributed system, nondeterminism is a problem that must be considered when designing distributed models, languages, and systems. Communication is perhaps the most obvious example of this; messages may be lost or arrive out-of-order. Finally, unlike in a local environment where failure returns control to the caller, failure may not be reported or the response may simply vanish. Because of this, distributed communication must be designed expecting partial failure, and be able to “fail gracefully”.

Several methods have been developed to deal with the problem of partial failure. One method, made popular with batch processing and MapReduce style frameworks, is to remember the series of computations needed to obtain a result and recompute the result in the case of failure. Systems such as MapReduce, Spark, GraphX, and Spark Streaming use this model, as well as implement optimizations to make it fast. Another method of dealing with partial failure is the two phase commit. To perform a change of state across many components, first a logically central “leader” checks to see if all components are ready to perform and action. If all reply “yes,” the action is committed. Otherwise, as in the case of partial failure, no changes are committed. Two phase commit ensures that state is not changed in a partial manner. Another solution to partial failure is redundancy, or replication. If one replica of a computation fails, the others may survive and continue. Replication can also be used to improve performance, as in MapReduce and Spark Streaming. Checkpoint and restore has also been implemented as a way to recover from partial failure. By serializing a recent “snapshot” of state to stable storage, recomputing current state is made cheap. This is the primary method of partial failure in RDD-based systems. In other systems, like Argus, objects are reconstructed from state that is automatically or manually serialized to disk.

Consistency (Concurrency)

If computing on shared data can be avoided, parallel computations will not be bottlenecked by serialized accesses. Unfortunately, there are many instances where operating on shared data is necessary. While problems with shared data can be dealt with fairly simply in the local case, distribution introduces problems that make consistency more complex.

In local computing, enforcing consistency is fast and straightforward. Traditionally, a piece of data is protected by another piece of data called a lock. To operate on the data, a concurrent process acquires the lock, makes its changes, then releases the lock. Because the data is either located in on-board memory or an on-chip cache, passing the shared data around is relatively fast. As in the case of partial failure, a central resource manager (the OS) is present and can respond to a failed process that has obtained a lock.

In a distributed environment, coordination and locking is more difficult. First, because of the lack of a central resource manager, there needs to be a way of preserving or recovering the state of shared data in the case of failure. The problem of acquiring locks also becomes harder due to partial failure and higher latency. Synchronization protocols must expect and be able to handle failure.

To deal with operations on shared data, there are a few standard techniques. A sequencer can be used to serialize requests to a shared piece of data. When a process on a machine wants to write to shared data, it sends a request to a logically central process called a sequencer. The sequencer takes all incoming requests and serializes them, and sends the serialized operations (in order) to all machines with a copy of the data. The shared data will then undergo the same sequence of transformations on each machine, and therefore be consistent. A similar method for dealing with consistency is the message queue. In the actor model, pieces of an application are represented as actors which respond to requests. Actors may use message queues which behave similarly to sequencers. Incoming method calls or requests are serialized in a queue which the actor can use to process requests one at a time. Finally, some systems take advantage of the semantics of operations on shared data, distinguishing between read-only operations and write operations. If an operation is determined to be read-only, the shared data can be distributed and accessed locally. If an operation writes to shared data, further synchronization is required.

Unfortunately, none of these techniques can survive a network partition. Consistency requires communication, and a partitioned network will prevent updates to state on one machine from propagating. Distributed systems therefore may be forced by other requirements to loosen their requirement of consistency. Below, the CAP theorem formalizes this idea.

Latency

Latency is another major problem that is unique to distributed computing. Unlike the other problems discussed in this section, latency does not necessarily affect program correctness. Rather, it is a problem that impacts application performance, and can be a source of nondeterminism.

In the case of local computing, latency is minimal and fairly constant. Although their may be subtle timing differences that arise from contention from concurrent processes, these fluctuations are relatively small. As well, machine hardware is constant. There are no changes to the latency of communication channels on a single machine.

Distribution of computation introduces a network topology which changes many of the underlying assumptions around latency. This topology significantly (orders of magnitude) increases the latency of communication, as well as introduces a source of nondeterminism. At any time, routing protocols or hardware changes (or both) may cause the latency between two machines to change. Therefore, distributed applications may not rely on specific timings of communication in order to function. Distributed processes may also be more restricted. Because communication across the network is costly, applications may necessarily be designed to minimize communication.

A more subtle (and sinister) problem with increased latency and the network is the inability of a program to distinguish between a slow message and a failed message. This situation is analogous to the halting problem, and forces distributed applications to make decisions about when a message, link, or node has “failed.”

Several methods have been developed to cope with the latency of communication. Static and dynamic analysis may be performed on communication patterns so that entities that communicate frequently are more proximate than those that communicate infrequently. Another approach that has been used is data replication. If physically separate entities all need to perform reads on a piece of data, that data can be replicated and read from local hardware. Another approach is pipelining; a common example of this is in some flavors of the HTTP protocol. Pipelining requests allows a process to continue with other work, or issue more requests without blocking for the response of each request. Pipelining lends itself to an asynchronous style of programming, where a callback can be assigned to handle the results of a request. Futures and promises have built on this programming style, allowing computations to be queued, and performed when the value of a future or promise is resolved.

The CAP Theorem

Indeed, the three problems outlined above are not independent, and a solution for one may come at the cost of amplifying the effects of another. For example, let’s suppose when a request to our system arrives, a response should be issued as soon as possible. Here, we want to minimize latency. Unfortunately, this may come at the cost of consistency. We are forced to either (1) honor latency and send a possibly inconsistent result, or (2) honor consistency and wait for the distributed system to synchronize before replying.

The CAP theorem (Gilbert & Lynch, 2002) formalizes this notion. CAP stands for Consistency, Availability, and tolerance to Partitioning. The theorem states that a distributed system may only have two of these three properties.

Since its introduction, experience suggests this theorem is not as rigid as was originally proposed (Brewer, 2012). In practice, for example, rareness of network partitioning makes satisfaction of all three easier. As well, advancements in consistency models, such as CRDT’s (Shapiro, Preguiça, Baquero, & Zawirski, 2011), make balancing consistency and availability flexible to the requirements of the system.

Three Major Approaches to Distributed Languages

Clearly, there are problems present in distributed programming that prevent traditional local programming models from applying directly to distributed environments. Languages and systems built for writing distributed applications can be classified into three categories: distributed shared memory, actors, and dataflow. Each model has strengths and weaknesses. Here, we describe each model and provide examples of languages and systems that implement them.

Distributed Shared Memory

Virtual memory provides a powerful abstraction for processes. It allows each process running on a machine to believe it is the sole user of the machine, as well as provide each process with more (or less) memory addresses than may be physically present. The operating system is responsible for mapping virtual memory addresses to physical ones and swapping addresses to and from disk.

Distributed shared memory (DSM) takes the virtual memory abstraction one step further by allowing virtual addresses to be mapped to physical memory regions on remote machines. Given such an abstraction, programs can communicate simply by reading from and writing to shared memory addresses. DSM is appealing because the programming model is the same for local and distributed systems. However, it requires an underlying system to function properly. Mirage, Orca, and Linda are three systems that use distributed shared memory to provide a distributed programming model.

Mirage (1989)

Mirage is an OS-level implementation of DSM. In Mirage, regions of memory known as segments are created and indicated as shared. A segment consists of one or more fixed-size pages. Other local or remote processes can attach segments to arbitrary regions of their own virtual address space. When a process is finished with a segment, the region can be detached. Requests to shared memory are transparent to user processes. Faults occur on the page level.

Operations on shared pages are guaranteed to be coherent; after a process writes to a page, all subsequent reads will observe the results of the write. To accomplish this, Mirage uses a protocol for requesting read or write access to a page. Depending on the permissions of the current “owner” of a page, the page may be invalidated on other nodes. The behavior of the protocol is outlined by the table below.

| State of Owner | State of Requester | Clock Check? | Invalidation? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reader | Reader | No | No |

| Reader | Writer | Yes | Yes, Requester is possibly sent current version of the page |

| Writer | Reader | Yes | No, Owner is demoted to Reader |

| Writer | Writer | Yes | Yes |

Crucially, the semantics of this protocol are that at any time there may only be either (1) a single writer or (2) one or more readers of a page. When a single writer exists, no other copies of the page are present. When a read request arrives for a page that is being written to, the writer is demoted to a reader. These two properties ensure coherence. Many read copies of a page may be present, both to minimize network traffic and provide locality. When a write request arrives for a page, all read instances of the page are invalidated.

To ensure fairness, the system associates each page with a timer. When a request is honored for a page, the timer is reset. The timer guarantees that the page will not be invalidated for a minimum period of time. Future request that result in invalidation or demotion (writer to reader) are only honored if the timer is satisfied.

Orca (1992)

Orca is a programming language built for distribution and is based on the DSM model. Orca expresses parallelism explicitly through processes. Processes in Orca are similar to procedures, but are concurrent instead of serial. When a process is forked, it can take parameters that are either passed as a copy of the original data, or passed as a shared data-object. Processes communicate through these shared objects.

Shared data objects in Orca are similar to objects in OOP. An object is defined abstractly by a name and a set of interfaces. An implementation of the object defines any private data fields as well as the interfaces (methods). Importantly, these interfaces are guaranteed to be indivisible, meaning that simultaneous calls to the same interface are serializable. Although serializability alone does not eliminate indeterminism from Orca programs, it keeps the model simple while it allows programmers to construct richer, multi-operation locks for arbitrary semantics and logic.

Another key feature of Orca is the ability to express symbolic data structures as shared data objects. In Orca, a generic graph type is offered as a first-class data-object. Because operations are serializable at the method level, the graph data-object can offer methods that span multiple nodes while still retaining serializability.

Linda (1993)

Linda is a programming model based on DSM. In Linda, shared memory is known as the tuple space; the basic unit of shared data is the tuple. Instead of processes reading and writing to shared memory addresses, processes can insert, extract, or copy entries from the tuple space. Under the Linda model, processes communicate and distribute work through tuples.

A Linda tuple is not a fixed size; it can contain any combination of primitive data types and values. To insert a tuple into the space, the fields of the tuple are fully evaluated before insertion. A process can decide to evaluate a tuple serially, or spin up a background task to first evaluate the fields, then insert the tuple. To retrieve a tuple from the space, a template tuple is provided that contains a number of fixed fields to match against, as well as formals that are “filled in” by the tuple that matches the search. If many tuples match the template, one is selected arbitrarily. When retrieving a tuple, the tuple may be left in the tuple space or removed.

In practice, the tuple space is disjointly distributed among the nodes in the cluster. The number and type of elements in a tuple defines the tuple’s class. All requests made for a particular class of tuple are sent through a rendezvous point, which provides a logically central way of performing book keeping about tuples. The rendezvous services requests for insertion and deletions of all tuples of a class. In the most basic implementation of Linda, each rendezvous point is located on a single participating node in the cluster.

Actor / Object model

Unlike DSM, communication in the actor model is explicit and exposed through message passing. Messages can be synchronous or asynchronous, point-to-point or broadcast style. In the actor model, concurrent entities do not share state as they do in DSM. Each process, object, actor, etc., has its own address space. The model maps well to single multicore machines as well as to clusters of machines. Although an underlying system is required to differentiate between local and remote messages, the location of processes, objects, or actors can be transparent to the application programmer. Erlang, Emerald, Argus, and Orleans are just a few of many implementations of the actor model.

Emerald (1987)

Emerald is a distributed programming language based around a unified object model. Programs in Emerald consist of collections of Objects. Critically, Emerald provides the programmer with a unified object model so as to abstract object location from the invocation of methods. With that in mind, Emerald also provides the developer with the tools to designate explicitly the location of objects.

Objects in Emerald resemble objects in other OOP languages such as Java. Emerald objects expose methods to implement logic and provide functionality, and may contain internal state. However, their are a few key differences between Emerald and Java Objects. First, objects in Emerald may have an associated process which starts after initialization. In Emerald, object processes are the basic unit of concurrency. Additionally, an object may not have an associated process. Objects that do not have a process are known as passive and more closely resemble traditional Java objects; their code is executed when called by processes belonging to other objects. Second, processes may not touch internal state (members) of other objects. Unlike Java, all internal state of Emerald objects must be accessed through method calls. Third, objects in Emerald may contain a special monitor section which can contain methods and variables that are accessed atomically. If multiple processes make simultaneous calls to a “monitored” method, the calls are effectively serialized.

Emerald also takes an OOP approach to system upgrades. With a large system, it may not be desirable to disable the system, recompile, and re-launch. Emerald uses abstract types to define sets of interfaces. Objects that implement such interfaces can be “plugged in” where needed. Therefore, code may be dynamically upgraded, and different implementations may be provided for semantically similar operations.

Argus (1988)

Argus is a distributed programming language and system. It uses a special kind of object, called a guardian, to create units of distribution and group highly coupled data and logic. Argus procedures are encapsulated in atomic transactions, or actions, which allow operations that encompass multiple guardians to exhibit serializability. The presence of guardians and actions was motivated by Argus’ use as a platform for building distributed, consistent applications.

An object in Argus is known as a guardian. Like traditional objects, guardians contain internal data members for maintaining state. Unique to Argus is the distinction between volatile and stable data members. To cope with crashes, data members that are stable are periodically serialized to disk. When a guardian crashes and is restored, this serialized state is used to reconstruct guardians. Like in Emerald, internal data members may not be accessed directly, but rather through handlers. Guardians are interacted with through methods known as handlers. When a handler is called, a new process is created to handle the operation. Additionally, guardians may contain a background process for performing continual work.

Argus encapsulates handler calls in what it calls actions. Actions are designed to solve the problems of consistency, synchronization, and fault tolerance. To accomplish this, actions are serializable as well as total. Being serializable means that no actions interfere with one another. For example, a read operation that spans multiple guardians either “sees” the complete effect of a simultaneous write operation, or it sees nothing. Being total means that write operations that span multiple guardians either fully complete or fully fail. This is accomplished by a two-phase commit protocol that serializes the state of all guardians involved in an action, or discards partial state changes.

Erlang (2000)

Erlang is a distributed language which combines functional programming with message passing. Units of distribution in Erlang are processes. These processes may be co-located on the same node or distributed amongst a cluster.

Processes in Erlang communicate by message passing. Specifically, a process can send an asynchronous message to another process’ mailbox. At some future time, the receiving process may enter a receive clause, which searches the mailbox for the first message that matches one of a set of patterns. The branch of code that is executed in response to a message is dependent on the pattern that is matched.

In general, an application written in Erlang is separated into two broad components: workers and monitors.

Workers are responsible for application logic.

Erlang offers a special function link(Pid) which allows one process to monitor another.

If the process indicated by Pid fails, the monitor process will be notified and is expected to handle the error.

Worker processes are “linked” by monitor processes which implement the fault-tolerance logic of the application.

Erlang, first implemented in Prolog, has the features and styles of a functional programming language. Variables in Erlang are immutable; once assigned a value, they cannot be changed. Because of this, loops in Erlang are written as tail recursive function calls. Although this at first seems like a flawed practice (to traditional procedural programmers), tail recursive calls do not grow the current stack frame, but instead replace it. It is worth noting that stack frame growth is still possible, but if the recursive call is “alone” (the result of the inner function is the result of the outer function), the stack will not grow.

Orleans (2011)

Orleans is a programming model for distributed computing based on actors. An Orleans program can be conceptualized as a collection of actors. Because Orleans is intended as a model for building cloud applications, actors do not spawn independent processes as they do in Emerald or Argus. Rather, Orleans actors are designed to execute only when responding to requests.

As in Argus, Orleans encapsulates requests (root function calls) within transactions. When processing a transaction, function calls may span many actors. To ensure consistency in the end result of a transaction, Orleans offers another abstraction, activations, to allow each transaction to operate on a consistent state of actors. An activation is an instance of an actor. Activations allow (1) consistent access to actors during concurrent transactions, and (2) high throughput when an actor becomes “hot.” Consistency is achieved by only allowing transactions to “touch” activations of actors that are not being used by another transaction. High throughput is achieved by spawning many activations of an actor for handling concurrent requests.

For example, suppose there is an actor that represents a specific YouTube video.

This actor will have data fields like title, content, num_views, etc.

Suppose their are concurrent requests (in turn, transactions) for viewing the video.

In the relevant transaction, the num_views field is incremented.

Therefore, in order to run the view requests concurrently, two activations (or copies) of the actor are created.

Because there is concurrency within individual actors, Orleans also supports means of state reconciliation. When concurrent transactions modify different activations of an actor, state must eventually be reconciled. In the case of the above example, it may not be necessary to know immediately the exact view count of a video, but we would like to be able to know this value eventually. To accomplish reconciliation, Orleans provides data structures that can be automatically merged. As well, the developer can implement arbitrary logic for merging state. In the case of the YouTube video, we would want logic to determine the delta of views since the start of the activation, and add that to the actors’ sum.

Dataflow model

In the dataflow model, programs are expressed as transformations on data. Given a set of input data, programs are constructed as a series of transformations and reductions. Computation is data-centric, and expressed easily as a directed acyclic graph (DAG). Unlike the DSM and actor models, processes are not exposed to the programmer. Rather, the programmer designs the data transformations, and a system is responsible for initializing processes and distributing work across a system.

MapReduce (2004)

MapReduce is a model and system for writing distributed programs that is data-centric. Distributed programs are structured as series of Map and Reduce data transformations. These two primitives are borrowed from traditional functional languages, and can be used to express a wide range of logic. The key strength of this approach is that computations can be reasoned about and expressed easily while an underlying system takes care of the “dirty” aspects of distributed computing such as communication, fault-tolerance, and efficiency.

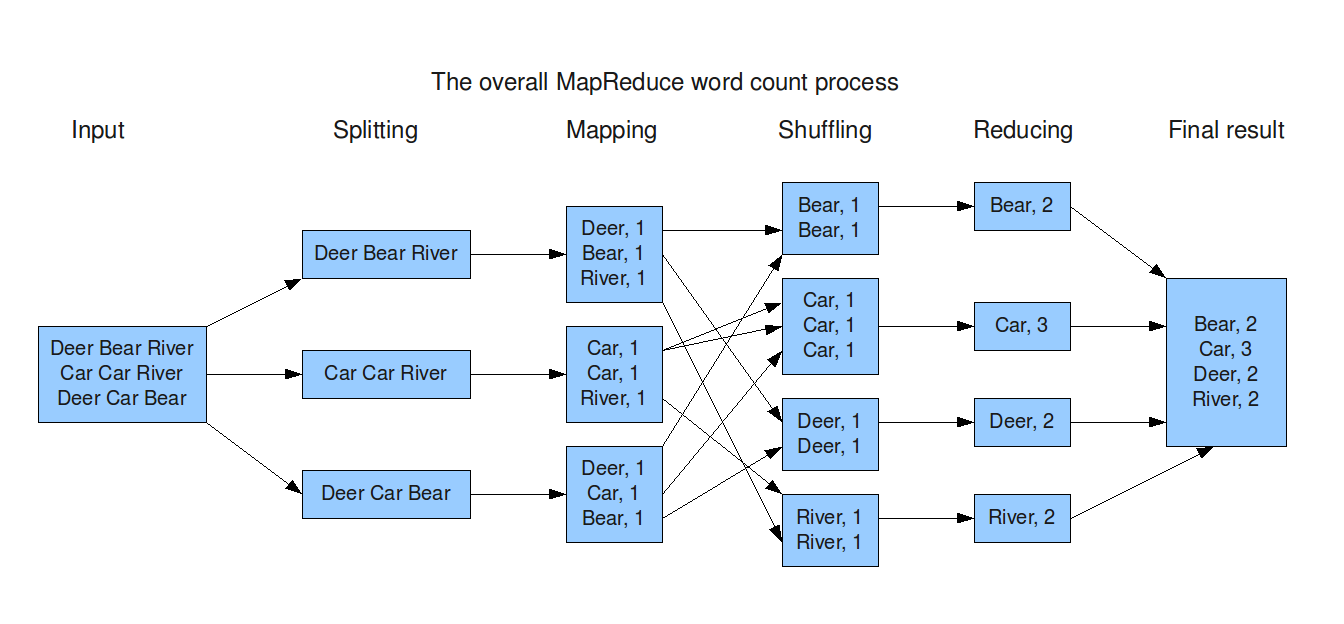

A MapReduce program consists of a few key stages. First, the data is read from a filesystem or other data source as a list of key-value pairs. These pairs are distributed amongst a set of workers called Mappers. Each mapper processes each element in its partition, and may output zero, one, or many intermediate key-value pairs. Then, intermediate key-value pairs are grouped by key. Finally, Reducers take all values pertaining to an intermediate key and output zero, one, or many output key-value pairs. A MapReduce job may consist of one or many iterations of map and reduce.

Crucially, for each stage the programmer is only responsible for programming the Map and Reduce logic. The underlying system (in the case of Google, a C++ library), handles distributing input data and shuffling intermediate entries. Optionally, the user can implement custom logic for formatting input and output data.

An example program in MapReduce is illustrated below. First, the input file is partitioned and distributed to a set of worker nodes. Then, the map function transforms lines of the text file into key-value pairs in the format (< word >, 1). These intermediate pairs are aggregated by key: the word. In the reduce phase, the list of 1’s is summed to compute a wordcount for each word.

Discretized Streams (2012)

Discretized Streams is a model for processing streams data in real-time based on the traditional dataflow paradigm. Streams of data are “chunked” discretely based on a time interval. These chunks are then operated on as normal inputs to DAG-style computations. Because this model is implemented on top of the MapReduce framework Spark, streaming computations can be flexibly combined with static MapReduce computations as well as live queries.

Discretized Streams (D-Streams) are represented as a series of RDD’s, each spanning a certain time interval. Like traditional RDD’s, D-Streams offer stateless operations such as map, reduce, groupByKey, etc., which can be performed regardless of previous inputs and outputs. Unlike traditional RDD’s, D-Streams offer stateful operations. These stateful operations, such as runningReduce, are necessary for producing aggregate results for a possibly never-ending stream of input data.

Because the inputs are not known a priori, fault tolerance in streaming systems must behave slightly differently. For efficiency, the system periodically creates a checkpoint of intermediate data. When a node fails, the computations performed since the last checkpoint are remembered, and a new node is assigned to recompute the lost partitions from the previous checkpoint. Two other approaches to fault tolerance in streaming systems are replication and upstream backup. Replication is not cost effective as every process must be duplicated, and does not cover the case of all replicas failing. Upstream backup is slow as the system must wait for a backup node to recompute everything in order to recover state.

GraphX (2013)

Many real world problems are expressed using graphs. GraphX is a system built on top of the Spark MapReduce framework (Zaharia et al., 2012) that exposes traditional graph operations while internally representing a graph as a collection of RDD’s. GraphX exposes these operations through what it calls a Resilient Distributed Graph (RDG). Internally, an RDG is a collection of RDD’s that define a vertex split of a graph (Gonzalez, Low, Gu, Bickson, & Guestrin, 2012). Because they are built on top of RDD’s, RDG’s inherit immutability. When a transformation is performed, a new graph is created. In this way, fault tolerance in GraphX can be executed the same way as it is in vanilla Spark; when a fault happens, the series of computations is remembered and re-executed.

A key feature of GraphX is that it is a DSL library built on top of a GPL library. Because it uses the general purpose computing framework of Spark, arbitrary MapReduce jobs may be performed in the same program as more specific graph operations. In other graph-processing frameworks, results from a graph query would have to be written to disk to be used as input to a general purpose MapReduce job.

With GraphX, if you can structure your application logic as a series of graph operations, an implementation may be created on top of RDD’s. Because many real-world applications, like social media “connections,” are naturally expressed as graphs, GraphX can be used to create a highly scalable, fault-tolerant implementation.

Comparing Design

Here, we present a taxonomy which can be used to classify each of the examples. Among these distributed systems appear to be three major defining characteristics: level of implementation, granularity, and level of abstraction. Importantly, these characteristics are orthogonal and each present an opportunity for a design decision.

Level of Implementation

The programming model exposed by each of the examples is implemented at some level in the computer system. In Mirage, the memory management needed to enable DSM is implemented within the operating system. Mirage’s model of DSM lends itself to an OS implementation because data is shared by address. In other systems, such as Orca, Argus, and Erlang, the implementation is at the compiler level. These are languages that support distribution through syntax and programming style. Finally, some systems are implemented as libraries (e.g. Linda, MapReduce). In such cases, the underlying language is powerfull enough to support desired operations. The library is used to ease programmer burden and supply domain-specific syntax.

The pros and cons of different implementation stategies is discussed further under DSL’s as Libraries.

Granularity of Logic and State

The granularity of logic and state is another major characteristic of these systems. Generally, the actor and DSM models can be considered fine grain while the dataflow model is course grain.

The actor and DSM models can be considered fine grain because they can be used to define the logic and states of individual workers. Under the DSM model, an application may be composed of many separately compiled programs. Each of these programs captures a portion of the logic, communication being done through shared memory regions. Under the actor model, actors or objects may be used to wrap separate logic. These units of logic communicate through RPC or message-passing. The benefit to using the actor or DSM model is the ability to wrap unique, cohesive logic in modules. Unfortunately, this means that the application or library developer is responsible for handling problems such as scaling and process location.

The dataflow model can be considered course grain because the logic of every worker is defined by a single set of instructions. Workers proceed by receiving a partition of the data and the program, and executing the transformation. Crucially, each worker operates under the same logic.

To borrow an idea from traditional parallel programming, the actor/DSM model implements a multiple instruction multiple data (MIMD) architecture, whereas the dataflow model implements a single instruction multiple data (SIMD) architecture.

Level of Abstraction

Each of the examples of systems for distributed computing offer different levels of abstraction from problems like partial-failure. Depending on the requirements of the application, it may be sufficient to let the system handle these problems. In other cases, it may be necessary to be able to define custom logic.

In some systems, like Emerald, it is possible to specify the location of processes. When the communication patterns of the application are known, this can allow for optimizations on a per-application basis. In other systems, the system handles the resource allocation of processes. While this may ease development, the developer must trust the system to make the decision.

The actor and DSM models require the application developer to create and destroy individual processes. This means that either the application must contain logic for scaling, or a library must be developed to handle scaling. Systems that implement the dataflow model handle scaling automatically. An exception to this rule is Orleans, which follows the actor model but handles scaling automatically.

Final, fault tolerance is abstracted to varying degrees in these systems. Argus exposes fault tolerance to the programmer; object data members are labeled as volatile or stable. Periodically, these stable members are serialized to disk and can be used for object reconstruction. Other systems, especially those based on dataflow, fully abstract the problem of partial failure.

Thoughts on System Design

Domain-Specific Languages

The definition of a domain-specific language is a hot topic and there have been several attempts to concretely define what exactly it is.

Here is the definition as given by (Mernik, Heering, & Sloane, 2005):

Domain-specific languages are languages tailored to a specific application domain.

Another definition is offered (and commonly cited) by (van Deursen, Klint, & Visser, 2000):

A domain-specific language is a programming language or executable specification language that offers, through appropriate notations and abstractions, expressive power focused on, and usually restricted to, a particular problem domain.

Generally, I would refer to a domain-specific language (DSL) as a system, be it a standalone language, compiler extension, library, set of macros, etc., that is designed for a set of cohesive operations to be easily expressed.

For example, the Python Twitter library is designed for easily expressing operations that manage a Twitter account.

The problem in defining this term (I believe) is the the vagueness of the components domain and language. Depending on the classification, a set of problems designated in a certain domain may span a “wide” or “narrow” scope. For example, does “tweeting” qualify as a domain (within the Twitter library)? Would “social media sharing” qualify as a domain (containing the Twitter library)? For my purposes I will accept the definition of a domain as a “well-defined, cohesive set of operations.”

It is also difficult to come up with a definition for a language. A language may be qualified if it has its own compiler. An orthogonal definition qualifies a language by its style, as in the case of sets of macros. This confusion is why I adopt the even more vague term system in my own definition.

Distribution as a Domain

Given the examples of models and systems, I think it is reasonable to qualify distribution as a domain. Distributed computing has a unique set of problems, such as fault-tolerance, nondeterminism, network partitioning, and consistency that make it unique from parallel computing on a single machine. The languages, systems, and models presented here all are built to assist the developer in dealing with these problems.

DSL’s as Libraries

The examples given above demonstrate a trend. At first, systems designed to tackle the distribution domain were implemented as stand-alone languages. Later, these systems appear as libraries built on top of existing general-purpose languages. For many reasons, this style of system development is superior.

Domain Composition

Systems like GraphX and Spark Streaming demonstrate a key benefit of developing DSL’s as libraries: composition. When DSL’s are implemented on top of a common language, they may be composed. For example, a C++ math library may be used along with MapReduce to perform complex transformations on individual records. If the math library and MapReduce were individual languages with separate compilers, composition would be difficult or impossible. Further, the GraphX system demonstrates that domains exist at varying degrees of generality, and that building the library for one domain on top of another may result in unique and efficient solutions. DSL’s that are implemented as full languages with unique compilers are unattractive because existing libraries that handle common tasks must be re-written for the new language.

Ecosystem

Another problem that drives DSL development towards libraries is ecosystem. In order for a DSL to be adopted, there must be a body of developers that can incorporate the DSL into existing systems. If either (1) the DSL does not incorporate well with existing code bases or (2) the DSL requires significant investment to learn, adoption will be less likely.

References

- Mernik, M., Heering, J., & Sloane, A. M. (2005). When and how to develop domain-specific languages. ACM Computing Surveys, 37(4), 316–344.

- Armstrong, J. (2010). Erlang. Communications of the ACM, 53(9), 68–75.

- van Deursen, A., Klint, P., & Visser, J. (2000). Domain-Specific Languages: An Annotated Bibliography. Sigplan Notices, 35(6), 26–36.

- Liskov, B. (1988). Distributed Programming in Argus. Communications of the ACM, 31(3), 300–312.

- Black, A., Hutchinson, N., Jul, E., Levy, H., & Carter, L. (1987). Distribution and Abstract Types in Emerald. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering, 1, 65–76.

- Waldo, J., Wyant, G., Wollrath, A., & Kendall, S. (1997). A note on distributed computing. In Mobile Object Systems Towards the Programmable Internet (pp. 49–64). Springer.

- Nitzberg, B., & Lo, V. (1991). Distributed shared memory: A survey of issues and algorithms. Distributed Shared Memory-Concepts and Systems, 42–50.

- Zaharia, M., Chowdhury, M., Das, T., Dave, A., Ma, J., McCauley, M., … Stoica, I. (2012). Resilient distributed datasets: A fault-tolerant abstraction for in-memory cluster computing. In Proceedings of the 9th USENIX conference on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (pp. 2–2). USENIX Association.

- Dean, J., & Ghemawat, S. (2008). MapReduce: simplified data processing on large clusters. Communications of the ACM, 51(1), 107–113.

- Gonzalez, J. E., Low, Y., Gu, H., Bickson, D., & Guestrin, C. (2012). Powergraph: Distributed graph-parallel computation on natural graphs. In Presented as part of the 10th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 12) (pp. 17–30).

- Brewer, E. (2012). CAP twelve years later: How the" rules" have changed. Computer, 45(2), 23–29.

- Gilbert, S., & Lynch, N. (2002). Brewer’s conjecture and the feasibility of consistent, available, partition-tolerant web services. ACM SIGACT News, 33(2), 51–59.

- Shapiro, M., Preguiça, N., Baquero, C., & Zawirski, M. (2011). Conflict-free replicated data types. In Symposium on Self-Stabilizing Systems (pp. 386–400). Springer.