ACIDic to BASEic: How the database pH has changed

The ACIDic Database Systems

Relational Database Management Systems are the most ubiquitous database systems for persisting state. Their properties are defined in terms of transactions on their data. A database transaction can be either a single operation or a sequence of operations, but is treated as a single logical operation on the data by the database. The properties of these transactions provide certain guarantees to the application developer. The acronym ACID was coined by Andreas Reuter and Theo Härder in 1983 to describe them.

-

Atomicity guarantees that any transaction will either complete or leave the database unchanged. If any operation of the transaction fails, the entire transaction fails. Thus, a transaction is perceived as an atomic operation on the database. This property is guaranteed even during power failures, system crashes and other erroneous situations.

-

Consistency guarantees that any transaction will always result in a valid database state, i.e., the transaction preserves all database rules, such as unique keys.

-

Isolation guarantees that concurrent transactions do not interfere with each other. No transaction views the effects of other transactions prematurely. In other words, they execute on the database as if they were invoked serially (though a read and write can still be executed in parallel).

-

Durability guarantees that upon the completion of a transaction, the effects are applied permanently on the database and cannot be undone. They remain visible even in the event of power failures or crashes. This is done by ensuring that the changes are committed to disk (non-volatile memory).

ACIDity implies that if a transaction is complete, the database state is structurally consistent (adhering to the rules of the schema) and stored on disk to prevent any loss.

Because of the strong guarantees this model simplifies the life of the developer and has been traditionally the go to approach in application development. It is instructive to examine how these properties are enforced.

Single node databases can simply rely upon locking to ensure ACIDity. Each transaction marks the data it operates upon, thus enabling the database to block other concurrent transactions from modifying the same data. The lock has to be acquired both while reading and writing data. The locking mechanism enforces a strict linearizable consistency, i.e. all transactions are performed in a particular sequence and invariants are always maintained by them. An alternative, multiversioning allows a read and write operation to execute in parallel. Each transaction which reads data from the database is provided the earlier unmodified version of the data that is being modified by a write operation. This means that read operations don’t have to acquire locks on the database. This enables read operations to execute without blocking write operations and write operations to execute without blocking read operations.

This model works well on a single node. But it exposes a serious limitation when too many concurrent transactions are performed. A single node database server will only be able to process so many concurrent read operations. The situation worsens when many concurrent write operations are performed. To guarantee ACIDity, the write operations will be performed in sequence. The last write request will have to wait for an arbitrary amount of time, a totally unacceptable situation for many real time systems. This requires the application developer to decide on a Scaling strategy.

Scaling transaction volume

To increase the volume of transactions against a database, two scaling strategies can be considered:

-

Vertical Scaling is the easiest approach to scale a relational database. The database is simply moved to a larger computer which provides more transactional capacity. Unfortunately, its far too easy to outgrow the capacity of the largest system available and it is costly to purchase a bigger system each time that happens.

-

Horizontal Scaling is a more viable option and can be implemented in two ways. Data can be segregated into functional groups spread across databases. This is called Functional Scaling. Data within a functional group can be further split across multiple databases, enabling functional areas to be scaled independently of one another for even more transactional capacity. This is called sharding.

Horizontal Scaling through functional partitioning enables high degree of scalability. However, the functionally separate tables employ constraints such as foreign keys. For these constraints to be enforced by the database itself, all tables have to reside on a single database server. This limits horizontal scaling. To work around this limitation the tables in a functional group have to be stored on different database servers. But now, a single database server can no longer enforce constraints between the tables. In order to ensure ACIDity of distributed transactions, distributed databases employ a two-phase commit (2PC) protocol.

-

In the first phase, a coordinator node interrogates all other nodes to ensure that a commit is possible. If all databases agree then the next phase begins, else the transaction is canceled.

-

In the second phase, the coordinator asks each database to commit the data.

2PC is a blocking protocol and updates can take from a few milliseconds up to a few minutes to commit. This means that while a transaction is being processed, other transactions will be blocked. So the application that initiated the transaction will be blocked. Another option is to handle the consistency across databases at the application level. This only complicates the situation for the application developer who is likely to implement a similar strategy if ACIDity is to be maintained.

The Distributed Concoction

A distributed application is expected to have the following three desirable properties:

-

Consistency - This is the guarantee of total ordering of all operations on a data object such that each operation appears indivisible. This means that any read operation must return the most recently written value. This provides a very convenient invariant to the client application. This definition of consistency is the same as the Atomicity guarantee provided by relational database transactions.

-

Availability - Every request to a distributed system must result in a response. However, this is too vague a definition. Determining whether a node failed in the process of responding, ran a really long computation to generate a response, or whether the request or response got lost due to network issues is generally impossible from the client’s perspective. This problem means that for all practical purposes, availability can be defined as the service responding to a request in a timely fashion, where the amount of delay an application can bear depends on the application domain.

-

Partition Tolerance - Partitioning is the loss of messages between the nodes of a distributed system. During a network partition, the system can lose arbitrary number of messages between nodes. A partition tolerant system will always respond correctly unless a total network failure happens.

The consistency requirement implies that every request will be treated atomically by the system even if the nodes lose messages due to network partitions. The availability requirement implies that every request should receive a response even if a partition causes messages to be lost arbitrarily.

The CAP Theorem

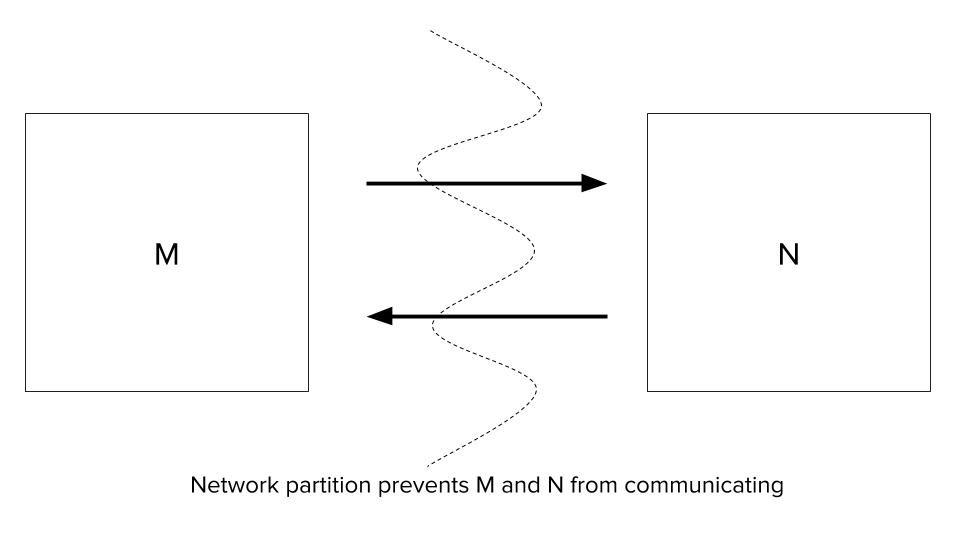

In the network above, all messages between the node set M and N are lost due to a network issue. The system as a whole detects this situation. There are two options:

-

Availability first - The system allows any application to read and write to data objects on these nodes independently even though they are not able to communicate. The application writes to a data object on node M. Due to network partition, this change is not propagated to replicas of the data object in N. Subsequently, the application tries to read the value of that data object and the read operation executes in one of the nodes of N. The read operation returns the older value of the data object, thus making the application state not consistent.

-

Consistency first - The system does not allow any application to write to data objects as it cannot ensure consistency of replica states. This means that the system is perceived to be unavailable by the applications.

If there are no partitions, clearly both consistency and availability can be guaranteed by the system. This observation led Eric Brewer to conjecture the CAP Theorem in an invited talk at PODC 2000. The CAP Theorem states:

It is impossible for a web service to provide the following three guarantees: Consistency, Availability, and Partition Tolerance

It is clear that the prime culprit here is network partitions. If there are no network partitions, any distributed service will be both highly available and provide strong consistency of shared data objects. Unfortunately, network partitions cannot be remedied in a distributed system.

Two of Three - Exploring the CAP Theorem

The CAP theorem dictates that the three desirable properties, consistency, availability and partition tolerance cannot be offered simultaneously. Let’s study if its possible to achieve two of these three properties.

Consistency and Availability

If there are no network partitions, then there is no loss of messages and all requests receive a response within the stipulated time. It is clearly possible to achieve both consistency and availability. Distributed systems over an intranet are an example of such systems.

Consistency and Partition Tolerance

Without availability, both of these properties can be achieved easily. A centralized system can provide these guarantees. The state of the application is maintained on a single designated node. All updates from the client are forwarded by the nodes to this designated node. It updates the state and sends the response. When a failure happens, then the system does not respond and is perceived as unavailable by the client. Distributed locking algorithms in databases also provide these guarantees.

Availability and Partition Tolerance

Without atomic consistency, it is very easy to achieve availability even in the face of partitions. Even if nodes fail to communicate with each other, they can individually handle query and update requests issued by the client. The same data object will have different states on different nodes as the nodes progress independently. This weak consistency model is exhibited by web caches.

Its clear that two of these three properties are easy to achieve in any distributed system. Since large scale distributed systems have to take partitions into account, will they have to sacrifice availability for consistency or consistency for availability? Clearly totally giving up either consistency or availability is too big a sacrifice.

The BASEic distributed state

When viewed through the lens of CAP theorem and its consequences on distributed application design, we realize that we cannot commit to perfect availability and strong consistency. But surely we can explore the middle ground. We can guarantee availability most of the time with occasional inconsistent view of the data. The consistency is eventually achieved when the communication between the nodes resumes. This leads to the following properties of the current distributed applications, referred to by the acronym BASE.

-

Basically Available services are those which are partially available when partitions happen. Thus, they appear to work most of the time. Partial failures result in the system being unavailable only for a section of the users.

-

Soft State services provide no strong consistency guarantees. They are not write consistent. Since replicas may not be mutually consistent, applications have to accept stale data.

-

Eventually Consistent services try to make application state consistent whenever possible.

Partitions and latency

Any large scale distributed system has to deal with latency issues. In fact, network partitions and latency are fundamentally related. Once a request is made and no response is received within some duration, the sender node has to assume that a partition has happened. The sender node can take one of the following steps:

- Cancel the operation as a whole. In doing so, the system is choosing consistency over availability.

- Proceed with the rest of the operation. This can lead to inconsistency but makes the system highly available.

- Retry the operation until it succeeds. This means that the system is trying to ensure consistency and reducing availability.

Essentially, a partition is an upper bound on the time spent waiting for a response. Whenever this upper bound is exceeded, the system chooses C over A or A over C. Also, the partition may be perceived only by two nodes of a system as opposed to all of them. This means that partitions are a local occurrence.

Handling Partitions

Once a partition has happened, it has to be handled explicitly. The designer has to decide which operations will be functional during partitions. The partitioned nodes will continue their attempts at communication. When the nodes are able to establish communication, the system has to take steps to recover from the partitions.

Partition mode functionality

When at least one side of the system has entered into partition mode, the system has to decide which functionality to support. Deciding this depends on the invariants that the system must maintain. Depending on the nature of problem, the designer may choose to compromise on certain invariants by allowing partitioned system to provide functionality which might violate them. This means the designer is choosing availability over consistency. Certain invariants may have to be maintained and operations that will violate them will either have to be modified or prohibited. This means the designer is choosing consistency over availability.

Deciding which operations to prohibit, modify or delay also depends on other factors such as the node. If the data is stored on the same node, then operations on that data can typically proceed on that node but not on other node.

In any event, the bottomline is that if the designer wishes for the system to be available, certain operations have to be allowed. The node has to maintain a history of these operations so that it can be merged with the rest of the system when it is able to reconnect. Since the operations can happen simultaneously on multiple disconnected nodes, all sides will maintain this history. One way to maintain this information is through version vectors.

Another interesting problem is to communicate the progress of these operations to the user. Until the system gets out of partition mode, the operations cannot be committed completely. Till then, the user interface has to faithfully represent their incomplete or in-progress status to the user.

Partition Recovery

When the partitioned nodes are able to communicate, they have to exchange information to maintain consistency. During the partition, both sides continued processing independently, but now the delayed operations on either side have to be performed and violated invariants have to be fixed. Given the state and history of both sides, the system has to accomplish the following tasks.

Consistency

During recovery, the system has to reconcile the inconsistency in state of both nodes. This is relatively straightforward to accomplish. One approach is to start from the state at the time of partition and apply operations of both sides in an appropriate manner, ensuring that the invariants are maintained. Depending on operations allowed during the partition phase, this process may or may not be possible. The general problem of conflict resolution is not solvable but a restricted set of operations may ensure that the system can always always merge conflicts. For example, Google Docs limits operations to style and text editing. But source-code control systems such as Concurrent Versioning System (CVS) may encounter conflict which require manual resolution.

Research has been done on techniques for automatic state convergence. Using commutative operations allows the system to sort the operations in a consistent global order and execute them. Though all operations can’t be commutative, for example - addition with bounds checking is not commutative. Mark Shapiro and his colleagues at INRIA have developed commutative replicated data types (CRDTs) that provably converge as operations are performed. By implementing state through CRDTs, we can ensure Availability and automatic state convergence after partitions.

Compensation

During partition, its possible for both sides to perform a series of actions which are externalized, i.e. their effects are visible outside the system. To compensate for these actions, the partitioned nodes have to maintain a history.

For example, consider a system in which both sides have executed the same order during a partition. During the recovery phase, the system has to detect this and distinguish it from two intentional orders. Once detected, the duplicate order has to be rolled back. If the order has been committed successfully then the problem has been externalized. The user will see twice the amount deducted from his account for a single purchase. Now, the system has to credit the appropriate amount to the user’s account and possibly send an email explaining the entire debacle. All this depends on the system maintaining the history during partition. If the history is not present, then duplicate orders cannot be detected and the user will have to catch the mistake and ask for compensation.

It would have been great if the duplicate order was not issued by the system in the first place. But the requirement to maintain system availability trumps consistency. Mistakes in such cases cannot always be corrected internally. But by admitting them and compensating for them, the system arguably exhibits equivalent behavior.

What’s the right pH for my distributed solution?

Whether an application chooses to be an ACIDic or BASEic service depends on the domain. An application developer has to consider the consistency-availability tradeoff on a case by case basis. ACIDic databases provide a very simple and strong consistency model making application development easy for domains where data inconsistency cannot be tolerated. BASEic systems provide a very loose consistency model, placing more burden on the application developer to understand the invariants and manage them carefully during partitions by appropriately limiting or modifying the operations.

References

https://neo4j.com/blog/acid-vs-base-consistency-models-explained/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eventual_consistency/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distributed_transaction https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distributed_database https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ACID http://searchstorage.techtarget.com/definition/data-availability https://aphyr.com/posts/288-the-network-is-reliable http://research.microsoft.com/en-us/um/people/navendu/papers/sigcomm11netwiser.pdf http://web.archive.org/web/20140327023856/http://voltdb.com/clarifications-cap-theorem-and-data-related-errors/ http://static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/en//archive/chubby-osdi06.pdf http://www.hpl.hp.com/techreports/2012/HPL-2012-101.pdf http://research.microsoft.com/en-us/um/people/navendu/papers/sigcomm11netwiser.pdf http://www.cs.cornell.edu/projects/ladis2009/talks/dean-keynote-ladis2009.pdf http://www.allthingsdistributed.com/files/amazon-dynamo-sosp2007.pdf https://people.mpi-sws.org/~druschel/courses/ds/papers/cooper-pnuts.pdf http://blog.gigaspaces.com/nocap-part-ii-availability-and-partition-tolerance/ http://stackoverflow.com/questions/39664619/what-if-we-partition-a-ca-distributed-system https://people.eecs.berkeley.edu/~istoica/classes/cs268/06/notes/20-BFTx2.pdf http://ivoroshilin.com/2012/12/13/brewers-cap-theorem-explained-base-versus-acid/ https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-difference-between-CAP-and-BASE-and-how-are-they-related-with-each-other http://berb.github.io/diploma-thesis/original/061_challenge.html http://dssresources.com/faq/index.php?action=artikel&id=281 https://saipraveenblog.wordpress.com/2015/12/25/cap-theorem-for-distributed-systems-explained/ https://www.infoq.com/articles/cap-twelve-years-later-how-the-rules-have-changed https://dzone.com/articles/better-explaining-cap-theorem http://www.julianbrowne.com/article/viewer/brewers-cap-theorem http://delivery.acm.org/10.1145/1400000/1394128/p48-pritchett.pdf?ip=73.69.60.168&id=1394128&acc=OPEN&key=4D4702B0C3E38B35%2E4D4702B0C3E38B35%2E4D4702B0C3E38B35%2E6D218144511F3437&CFID=694281010&CFTOKEN=94478194&acm=1479326744_f7b98c8bf4e23bdfe8f17b43e4f14231 http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=1394127.1394128 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eventual_consistency https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two-phase_commit_protocol https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ACID https://people.eecs.berkeley.edu/~brewer/cs262b-2004/PODC-keynote.pdf http://www.johndcook.com/blog/2009/07/06/brewer-cap-theorem-base/ http://searchsqlserver.techtarget.com/definition/ACID http://queue.acm.org/detail.cfm?id=1394128 http://www.dataversity.net/acid-vs-base-the-shifting-ph-of-database-transaction-processing/ https://neo4j.com/developer/graph-db-vs-nosql/#_navigate_document_stores_with_graph_databases https://neo4j.com/blog/aggregate-stores-tour/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eventual_consistency https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distributed_transaction https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distributed_database https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ACID http://searchstorage.techtarget.com/definition/data-availability https://datatechnologytoday.wordpress.com/2013/06/24/defining-database-availability/

- Haller, P., & Odersky, M. (2010). Capabilities for Uniqueness and Borrowing. In ECOOP 2010, Maribor, Slovenia, June 21-25, 2010. (pp. 354–378).

- Birrell, A. D., & Nelson, B. J. (1984). Implementing remote procedure calls. ACM Transactions on Computer Systems (TOCS), 2(1), 39–59.

- Wollrath, A., Riggs, R., & Waldo, J. (1996). A Distributed Object Model for the Java\^ T\^ M System.

- Pitt, E., & McNiff, K. (2001). Java. rmi: The Remote Method Invocation Guide. Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.

- Tanenbaum, A. S., & van Renesse, R. (1987). A critique of the remote procedure call paradigm.

- Kalia, A., Kaminsky, M., & Andersen, D. G. FaSST: Fast, Scalable and Simple Distributed Transactions with Two-Sided (RDMA) Datagram RPCs. In 12th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 16) (pp. 185–201). USENIX Association.

- Sandberg, R., Goldberg, D., Kleiman, S., Walsh, D., & Lyon, B. (1985). Design and implementation of the Sun network filesystem. In Proceedings of the Summer USENIX conference (pp. 119–130).

- Prunicki, A. (2009). Apache Thrift.

- Group, O. M. (1991). The Common Object Request Broker: Architecture and Specification. OMG Document Number 91.12.1.

- Google. gRPC. Retrieved from http://www.grpc.io/

- Ferguson, D. Exclusive .NET Developer’s Journal "Indigo" Interview with Microsoft’s Don Box. Retrieved from http://dotnet.sys-con.com/node/45908

- CORBA. CORBA-OMG. Retrieved from http://www.corba.org/

- Eriksen, M. (2013). Your server as a function. In Proceedings of the Seventh Workshop on Programming Languages and Operating Systems (p. 5). ACM.

- Bergstrom, E., & Pandey, R. (2007). Anycast-RPC for Wireless Sensor Networks. In 2007 IEEE International Conference on Mobile Adhoc and Sensor Systems (pp. 1–8). IEEE.

- Srinivasan, R. (1995). RFC 1831 - RPC: Remote procedure call protocol specification version 2.

- Mueller, J. (2015). Delving Into the Microservices Architecture. Retrieved from http://blog.smartbear.com/microservices/delving-into-the-microservices-architecture/

- White, J. E. (1975). High-level framework for network-based resource sharing.

- Tang, C., Chen, D. Q., Dwarkadas, S., & Scott, M. L. (2004). Integrating remote invocation and distributed shared state. In Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium, 2004. Proceedings. 18th International (p. 30). IEEE.

- Chen, D. Q., Dwarkadas, S., Parthasarathy, S., Pinheiro, E., & Scott, M. L. (2000). Interweave: A middleware system for distributed shared state. In International Workshop on Languages, Compilers, and Run-Time Systems for Scalable Computers (pp. 207–220). Springer.

- Chen, D. Q., Tang, C., Chen, X., Dwarkadas, S., & Scott, M. L. (2002). Multi-level shared state for distributed systems. In Parallel Processing, 2002. Proceedings. International Conference on (pp. 131–140). IEEE.

- Kumar, K., Liu, J., Lu, Y.-H., & Bhargava, B. (2013). A survey of computation offloading for mobile systems. Mobile Networks and Applications, 18(1), 129–140.

- Ibis. Ibis Communication middleware. Retrieved from https://www.cs.vu.nl/ibis/rmi.html

- Zhou, Z., Zhang, H., Ye, L., & Du, X. (2016). Cuckoo: flexible compute-intensive task offloading in mobile cloud computing. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing.

- Cuervo, E., Balasubramanian, A., Cho, D.-ki, Wolman, A., Saroiu, S., Chandra, R., & Bahl, P. (2010). MAUI: making smartphones last longer with code offload. In Proceedings of the 8th international conference on Mobile systems, applications, and services (pp. 49–62). ACM.

- Merkel, D. (2014). Docker: lightweight linux containers for consistent development and deployment. Linux Journal, 2014(239), 2.

- Sarma, S. E., Weis, S. A., & Engels, D. W. (2002). RFID systems and security and privacy implications. In International Workshop on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems (pp. 454–469). Springer.

- Oracle. Overview of Secure RPC. Retrieved from https://docs.oracle.com/cd/E23823_01/html/816-4557/auth-2.html

- Kenton. Is Cap’n Proto Secure? Retrieved from https://capnproto.org/faq.html#is-capn-proto-secure

- Caniou, Y., Caron, E., Desprez, F., Nakada, H., Tanaka, Y., & Seymour, K. (2008). High performance GridRPC middleware. Recent Developments in Grid Technology and Applications, Nova Science Publishers, 141–181.

- YarKhan, A., Dongarra, J., & Seymour, K. (2007). Gridsolve: The evolution of a network enabled solver. In Grid-Based Problem Solving Environments (pp. 215–224). Springer.

- Hardt, M., Seymour, K., Dongarra, J., Zapf, M., & Ruitter, N. V. (2012). Interactive Grid-access using Gridsolve and giggle. Computing and Informatics, 27(2), 233–248.

- Tanaka, Y., Nakada, H., Sekiguchi, S., Suzumura, T., & Matsuoka, S. (2003). Ninf-G: A reference implementation of RPC-based programming middleware for Grid computing. Journal of Grid Computing, 1(1), 41–51.

- Armstrong, J., Virding, R., Wikström, C., & Williams, M. (1993). Concurrent programming in ERLANG.

- Surtani, M., & Ho, A. gRPC: The Story of Microservices at Square. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-2sWDr3Z0Wo

- Google. gRPC core APIs. Retrieved from https://github.com/grpc/grpc/tree/master/src/core

- Google. About gRPC. Retrieved from http://www.grpc.io/about/

- Google. gRPC Documentation. Retrieved from http://www.grpc.io/docs/

- Google. Google APIs. Retrieved from https://github.com/googleapis/googleapis/

- Taing, N. Remote Procedure Call (RPC). Retrieved from http://lycog.com/distributed-systems/remote-procedure-call/

- Trends, G. Remote Procedure Call (RPC). Retrieved from https://www.google.com/trends/explore?cat=31&date=today%2012-m&q=apache%20thrift,grpc&hl=en-US

- Google. GRPC Authentication. Retrieved from http://www.grpc.io/docs/guides/auth.html

- White, J. E. (1975). RFC 707: A high-level framework for network-based resource sharing. December.

- Postel, J., & White, J. E. (1974). RFC 674: Procedure call documents: Version 2.

- Schantz, R. (1975). RFC 684: Commentary on procedure calling as a network protocol.

- Google. GRPC Authentication. Quora. Retrieved from https://www.quora.com/Is-GRPC-better-than-Thrift

- Yu, L. Added service multiplexing support. Github. Retrieved from https://github.com/eleme/thriftpy/pull/88/commits/0877531f9246ca993c1d9af5d29cd009ee6ec7d4

- Thurlow, R. (2009). RFC 5531: RPC: Remote Procedure Call Protocol Specification Version 2.

- Srinivasan, R. (1995). RFC 1831: RPC: Remote Procedure Call Protocol Specification Version 2.

- Grosu, P., Abdul Rehman, M., Anderson, E., Pai, V., & Miller, H. gRPC. Programming Models for Distributed Computation. Github. Retrieved from http://dist-prog-book.com/chapter/1/gRPC.html

- Rouse, M. stub. WhatIs. Retrieved from http://whatis.techtarget.com/definition/stub

- Mandel, M. Scalable Realtime Microservices with Kubernetes and gRPC. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xb8u2s7cxzg&t=486s

- InsideGov. 2016 United States Budget Estimate. InsideGov. Retrieved from http://federal-budget.insidegov.com/l/119/2016-Estimate

- Waldo, J., Wyant, G., Wollrath, A., & Kendall, S. (1997). A note on distributed computing. In Mobile Object Systems Towards the Programmable Internet (pp. 49–64). Springer.

- Dewan, P. (2006). Synchronous vs Asynchronous. UNC. Retrieved from http://www.cs.unc.edu/ dewan/242/s07/notes/ipc/node9.html

- Asynchronous RPC. (2006). Microsoft. Retrieved from https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/windows/desktop/aa373550(v=vs.85).aspx

- Setia, S. Remote Object Invocation. QMU. Retrieved from https://cs.gmu.edu/ setia/cs707/slides/rmi-imp.pdf

- Weiner, D. (1999). XML-RPC. QMU. Retrieved from http://xmlrpc.scripting.com/spec.html

- Jones, M. (2014). XML-RPC. Quora. Retrieved from https://www.quora.com/What-is-the-difference-between-xml-rpc-and-soap

- Maheshwar, C. (2013). Apache THRIFT: A Much Needed Tutorial. Digital Madness. Retrieved from http://digital-madness.in/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/BSD_08_2013.8-18.pdf

- Twitter. (2016). Finagle-Quickstart. Twitter. Retrieved from https://twitter.github.io/finagle/guide/Quickstart.html

- Norman, S. (2015). Communication Fundamentals. SlideShare. Retrieved from http://slideplayer.com/slide/8555756/